|

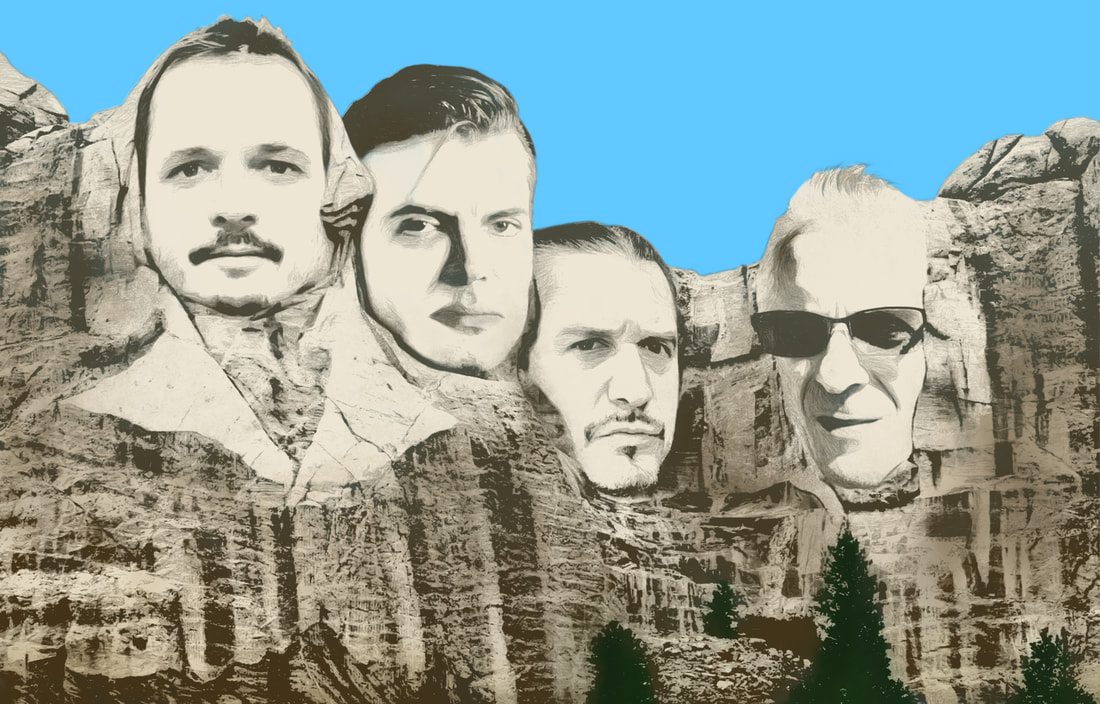

Interview by Parisa Eshrati Marking the twentieth anniversary of the band, Tomahawk return with their first album in eight years, the highly-anticipated Tonic Immobility on Ipecac Recordings. The group, featuring Duane Denison (The Jesus Lizard), Trevor Dunn (Mr. Bungle/Fantômas), Mike Patton (Faith No More/Mr. Bungle, etc.) and John Stanier (Helmet/Battles), bring together elements of Tomahawk's past into the present, while lyrically straddling the lines between a dystopian future and our new everyday pandemic reality. We caught up with guitarist Duane Denison to talk album themes, innovating his signature guitar sound, and finding hope even in these uncertain times. The process for the new album, Tonic Immobility, started a few years ago when you worked on demos and sent them over to Mike Patton. I thought that was a very fitting nod to how this band started in the first place with you two swapping demo tapes at shows. Obviously a lot has happened between then, but I’d be interested to hear your perspective on the 20th anniversary of Tomahawk, and how everything is similar yet completely different at the same time. It’s funny you mention that, because when the first album came out, it was right on the heels of 9/11. In fact, the release got delayed by that. John [Stanier], our drummer, was living in New York at the time and everyone was obviously stunned by what had happened. The album came out under this cloud of fear and paranoia. So here we are again, twenty years later living under extremely turbulent times. I mean, at least we recently had an election with an outcome that I’m personally happy with, but there’s the pandemic, the recent attack on the Capitol building, and just an awful fallout from there. We’ve come full circle, as you said, and things are different, but still very problematic in so many ways. We’re staying positive as a band, but still existing under this sort of weird cloud of fear, suspicion and paranoia. I imagine you all record distantly out of necessity since the band is spread out, but it’s interesting how the recording process unintentionally mirrored the album’s pandemic themes, seeing as how you were working distantly and in solitude. How do you think the recording process ultimately gave way to the themes of this album? We've always communicated by demos, but actually it's a common misconception that we do everything distantly. I'll record some ideas from home, but when we make the album, we get together. The first album we all met up in Nashville, the second one was in Los Angeles, and the guys have been coming to meet me in Nashville ever since. For this album, John and Trevor came to record here about four years ago. Mike had heard the demos but was too busy with other projects to work on them. We decided to start tracking, and let Mike get to them whenever he could. John and Trevor came to Nashville and you know, being the consummate professionals they are, had already learned the tunes. It didn't take much practice time to get it together, so we tracked it all here and then sent that off to Mike. He has a home studio, so during the first shutdown about a year ago, he was able to record and do his vocal parts and sample things. So yeah, for this album Mike did his parts from home, but otherwise we've always done it together. Although this album hits at a little bit of everything Tomahawk has released, it’s vastly different in that it has a very clean and clear atmosphere. There are far less vocal samples, and there’s a lot more space between sounds as opposed to layering the instrumentation. What attracted you to this new approach? You know, I've always preferred things more spacious, and Mike and I tend to not see eye-to-eye over that. He's kind of a "more is more" guy and I'm a "less is more" type of guy. So I guess with this one...I just got my way! [laughs] But really, I think he didn't want to do as many samples on this record and preferred to focus on the vocals and vocal harmonies. There's a fair amount of vocal dubs, but not much in the way of samples. I think it just suited the arrangements. We're letting the guitars and the instruments carry the atmosphere this time. It's nice to leave some space in there and leave some breathing room for the listener. It's easier to wander in through an open door than a door with clutter in the way, so it feels inviting in that sense. Let’s talk about some of the tracks on the album, starting with “Doomsday Fatigue”. It’s a classic Tomahawk song with a reference to Spaghetti Western sound, and it presents this great contrast of a cinematic atmosphere to pair with something as banal and depressingly mundane as pandemic exhaustion. I know you guys like to create music as a form of escape, so I'm curious if these two very contrasting ideas were paired to achieve an even more grandiose form of escapism. I totally see what you're saying, but we're not that clever [laughs]. I don't think we thought that far ahead with that particular song. However, there was intention with how the main theme is in a minor key guitar part; it comes snaking out, but in the middle of the song, it switches and goes a half-step up and suddenly turns into a major key when the keyboard part comes in. It kind of has an uplifting feeling in the middle, but not for long. Then it's right back into the minor key on the way out. So there are some contrasting ideas within "Doomsday Fatigue", but I think the idea is that it's not hopeless and that it's not going to be like this forever. Yes, we're all feeling it, but it doesn't mean it's the end of things. We can turn this around. Absolutely. You've said how this album presents an alternate reality to everything going on in the world, but at the same time, it's very confrontational and straightforward with what's going on. "Business Casual", for example, deals directly with the vapidness of American work life. Would you say then you’re drawing a line between escapism and pure avoidance? Yeah, in a sense. I feel like everyone has been so tapped out, myself included. I found the last four years so incredibly exhausting, waking up every single day to a president that won't stop tweeting these inflammatory remarks. There was just so much chaos to keep up with. But through all this mess, life goes on. People are going to work. They're putting on their business casual. And you know, people in America are so obsessed with their appearance. Aside from just clothes, there’s always been this history of dieting, types of workouts, exercise fads, etc. We've watched people go from dianetics to isometrics to aerobics to pilates... and then with dieting, it's a mess of high carb to low carb to keto. It's dizzying to keep track of! And all the while, you've got to wear your business casual. The song is very much a commentary on that, and this idea that there’s still this everyday life happening through all the chaos. The track “Predators and Scavengers” was inspired by watching wildlife chase each other in your backyard. Your guitar work here really mimics this scene, with muted riffs imitating the hunt and the faster riffs replicating the chase. It gets increasingly complex as the time signatures fluctuate, so I’m curious what these progressions relay about your reflections and how we’ve mirrored nature in this constant chase. Sometimes when I look out the window and see coyotes and raccoons and vultures chasing each other, I'm like...is this all? Do we all just fall into these categories of scavengers and predators? What does this say about us? What does it say about our society? That's the concept that drove the lyrics. Instead of doing the traditional verse-chorus-middle verse-chorus, it all leads to up to a single chorus in the middle. It all aims to the lyrics "Like scavengers and predators/all I ever see", so the message peaks out there, disappears, and slightly builds again, but you don't get another chorus. It leaves off with just the one message firmly placed in the middle with an uncertain ending. As far as the specific guitar work, I was trying to do this fast, agitated sound. I didn’t intentionally mimic the sound or the motions of the animals, but if that's what people hear then I think it's really cool it suggests that. As a musician, I think you're doing something right when people start interpreting your music in different ways. When people can hear something and it creates meaning to them, then that's great. It means I've done my job, so thank you. And of course, the closing track “Dog Eat Dog” really caps off on this theme. I know you’re a librarian and have a love for dystopian literature, so I want to compare this to one of your favorite books, J.G. Ballard’s High Rise, where those themes become quite literal. Tell us more about extrapolating these literary themes in your music, and where you see the lines between dystopia and reality meet these days. Well let me start by saying that I'm not trying to be negative or nihilistic just for the sake of it. It seems like there are a lot of that where bands are very fashionably nihilistic or negative, and then you meet these bands in person and they're nothing like that. They're actually quite happy-go-lucky, which I’ve always thought was odd. "Dog Eat Dog" on one hand could be seen as a commentary for the inherent, endless competition that you get in a capitalist world where you're constantly competing for jobs, money, housing and healthcare. It's like, what do we make of this? But at the same time, in the music video, it's very simple. You've got these morons beating each other to pieces, and then finally turning against their masters and becoming friends. So I like to comment on dystopia, but I'm not dwelling on it. I wish we could live in a utopia where everyone has their needs met and people's lives all have meaning other than just the endless pursuit of money, but it's going to take a lot of work to get there. Also wanted to congratulate you on another milestone, Jesus Lizard’s Goat turned thirty this month! Anything you want to say about that album thirty years in retrospect? It's hard to say, because it would've never occurred to me that thirty years later, people would still be talking about this record. It never occurred to any of us! Don't get me wrong, we knew at the time what we were making something different, but we weren’t really sure of what exactly we had created. It wasn't a typical hard rock album from that period. The guitars were kind of clean, there weren't big power chords, or the typical caterwauling, overblown, over-emotive vocalizing that became popular from the grunge scene in the '90s. That album went against the grain of what the trends were for that period. I remember listening to the final mixes in the studio with David [Yow, vocalist] and thinking, "Man...this is going to freak people out." I wasn't sure how I felt about it, then over time those songs caught on and people seemed to respond really well to that style. I never thought that it would be considered a classic album from that era, which some people seem to think it is now. Overall, I'm very, very humbled and so happy about it. Going off that, that album and your work in Jesus Lizard in general cemented your signature style. You’ve mentioned in previous interviews how you feel that you have to stay true to your sound, so how do you strike that balance of doing something tried and true while also staying innovative? That’s absolutely right, and well, it’s one of the hardest things to do. I mean, on one hand, you work your ass off to try and come up with a unique style that defines you, not only by what you do, but what you don't do. That's true in anything, whether you're a writer, a painter, a chef, it's not just what you do that makes you who you are, but what you don't do too. So it becomes hard, because you want to maintain some identity within your signature style and sound, but you can't just keep recycling the same ideas because then you're in a rut. The trick is to somehow absorb new influences and new ideas a little at a time and bring them out and mix it in with what you already do. There are some obvious examples with artists like Picasso or Stravinsky where you don't see them for awhile, and then they come out with a style completely different than anything they've done before. Well, they can get away with that, but I don't think I can. I think as a rock musician, if you come up with something that is completely different from what you've done, it seems artificial. It seems a little too contrived. So you have to find a way to mix in the new things with your own. It's really, very hard. At the same time, if you're writing new material, you shouldn't have any sort of preconceptions. You just have to intuitively write. You have to go with what you're feeling at the time. I think a lot of it just happens naturally. I've been doing this so long, and as you age, different things become important to you. As long as you're still mentally healthy, you can create new things that reflect where you are at that current point in your life. Somehow, I think I'm still doing that, so I guess I'm just lucky in that regard. I know it’s difficult to think of the future when everything is still so uncertain, but what might be next for Tomahawk? There’s not really too much on the horizon right now. Everything got pushed aside during the pandemic and now people are starting to put things back together, but as of right now, there are no plans for Tomahawk to do anything. The Jesus Lizard guys and I still talk all the time, so who knows, something might happen there in the future. I want to keep doing music, and I’m sure we all do, so hopefully now that things are slowly getting back up and running, there’ll be an audience waiting for when we return. ---

Purchase Tonic Immobility on bandcamp or Ipecac Recordings. Related reading on T&E: Creating Optimism through Orchestrational Abstraction: An Interview with Anthony Pateras of tētēma

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Interview Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed