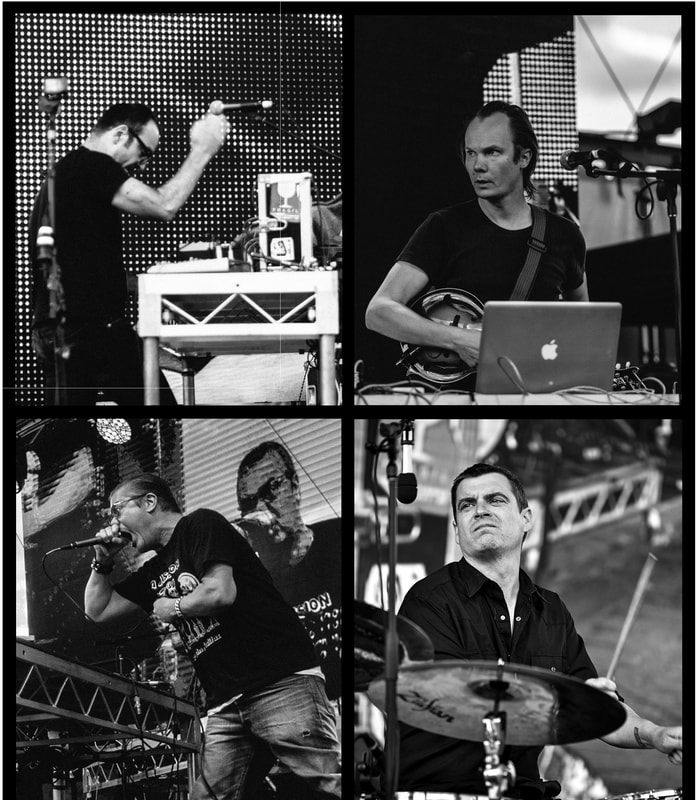

Creating Optimism through Orchestrational Abstraction: An Interview with Anthony Pateras of tētēma5/4/2020 Interview by Parisa Eshrati tētēma is the cross continent tour-de-force project featuring composer and songwriter Anthony Pateras and vocalist Mike Patton (Faith No More, Mr. Bungle, etc.), Their recently released second LP, Necroscape, is a synthesis of musique concrète, analogue tape loop recordings, industrial noise, complex time signatures, and heavy experimental grooves. The result is a brilliant avant-garde release brimming with intricacies that create a challenging yet buoyant mood. In this interview, we caught up with Pateras to discuss the five year recording process, techniques used to create tabula rasa soundscapes, and finding optimism through experimentation. For the new album, Necroscape, you were essentially working in a framework outside of time and space. The recording and production took over the course of 5 years, and everyone collaborated internationally. How do the physical factors of creating this album play into the manipulation of time and space in the compositions? They seem to create waves of heightened tension and chaotic release, does that at all translate into the process of this record? I enjoy the superimposition of different spaces and places into a final, singular entity. Certainly the different circumstances, moods and sound worlds combine in ways which would be difficult to replicate in the traditional shared space of a recording studio. And frankly both are now abstract concepts (tradition and what a studio is). That all said, compositionally it was a very fungal thing. Things would rhizomatically shoot out of each other and provoke other directions to those originally envisioned. The breathing space this availed led to a long process of consideration, ultimately proposing: do I want to listen to this more than once? It became a process of maintaining my attention, maintaining my concentration, pivoting my relationship to the materials frequently, feeling like I was dancing with another person who wasn’t myself. Records like these spin like a vertiginous stroboscope where suddenly the right exit reveals itself for a split second, then you spend weeks trying to relocate the door with the golden handle. Let's talk a bit more about the writing and recording processes for the new record. How did the ideas, concepts and sounds change over the course of the 5 years that this album was being created? You talk about straying away from quantization while still creating idiosyncratic rhythms, how were you and drummer Will Guthrie able to achieve that while recording distantly? This record was very singular in its intention, in that I wanted to migrate a ‘rock’ language into the realm of musique concrète. Whether this would work or not was a mystery until I wrote in the very last automaton. It’s conceived as a singular, 40 minute listen, a series of movements giving different weight to various permutations, strengths and weaknesses of the band. Much the like the first album Geocidal, it was always thought of holistically; but also, I wanted each micro-element to hold its own in the broader picture, much like Nadia Boulanger’s assertion that if you pull a singular line out of a piece for large orchestra it should maintain its strength and cohesion. In terms of quantisation, this is yet another assumption sold to musicians by supposedly ‘creative’ corporations that everything has to look and sound a certain way. The only thing useful about quantisation is that it provides a solid reference point from which to escape. Being ‘in time’ is subjective at best, as time measured by the clock or watch (as McCluhan pointed out) is a completely arbitrary system which negates the very freedom of its essence and locks us into thinking and living in a certain, prescribed manner. You know, no one’s Abelton interface is going to end up in the Smithsonian like Dilla’s MPC. Hardware provides the flexibility and nuance of instrumental performance which new software can continue to breathlessly offer us in its press release, but in fact never deliver the humanity it promises. Just to clarify, I was present for all of the recordings, apart from Mike’s (which was not the case for the first album, I went to his place). I really enjoy how you describe Necroscape as an optimistic album, despite it being so intensely dissonant and experimental. It reminds me how Delia Derbyshire said, “I think a lot of people have a sort of block about electronic music, they think it must sound frightening and oppressive.” Can you elaborate on hearing optimism through discordant sounds, and how that reflects into the ethos of this album? Like time, what is perceived as dissonant is completely subjective and again, what is often referred to or labelled as dissonance is a result of (a) broader cultural conditioning through corporate agendas to monetise organised sound and (b) humanity’s need to label with value judgments what essentially are vibrations in the air. I love Delia Derbyshire, her curiosity, her joy in composing. That optimism she provides, if i can theorise for a second, comes from the relief that she was able to construct and execute her own world with the tools she had at hand. There is always a happiness and spaciousness to her music, not to mention a fantastic sense of humour combined with technical nuance. Pulseless electronic music is so extreme in that its (a) either based on very open harmonies with long reverbs, or (b) dissonant noise stuff which seems to be at core, childish and antisocial. Then you have these self-appointed middle class revolutionaries with clever booking agents just playing louder and bigger than everyone, amplifying their own ecstatic emptiness. This is really on the nose. My intention with the record was not to be loud and dissonant, contrary to what you say, it’s what I attempt with every record, which is to find something I may not have heard before in this particular way, with these particular resources. The fact that there’s a so-called rock star upfront means nothing. Mike [Patton] is a good singer, he can make this music better, that’s all that matters to me. In terms of optimism, anything which offers possibilities and explores a different space is optimistic to me. On the contrary, anything which repeats something that’s already been done but much worse (as we hear so often), is anathema. It makes me feel as though culture has been crushed by the weight of capital to the point where we can’t even have our own ideas any more. That’s terrifying and we have to resist that at all costs. Your intention of this record was to create a tabula rasa soundscape, making the listener at a loss for their surroundings and wonder where each sound is coming from. Can you elaborate more on the techniques you used to create this type of disorientation? You direct Mike's voice as a reference point for the natural world, was this intended to put an emphasis on the lyrics or just as an anchor for the listener to have some sense of stability? I have a deep interest in orchestrational abstraction. I enjoy bringing instruments into a world of hallucination with minimal use of effects, if any. I’m not interested in a kind of facile, synthesised transformation of acoustic timbre via electronic means. A convincing elevation of the source via these methods is rare and takes a lot of effort. Instruments played well simply sound great, that’s it. So in terms of constructing what you describe, it’s all about context. For me it’s about positioning idiosyncratic constellations of sound where suddenly you find yourself somewhere else. With electronic music, you can go anywhere. Why anyone uses arpeggiators is beyond me. You have an entire universe of tuning and rhythmic possibility at your fingertips and you wanna play me shitty toccatas in F minor with a square wave? So, I mean, again, it’s more about knowing what to stay away from rather than knowing what you’re trying to get at. I mean at some point you just have to trust your ears and go with what you want. Whether that provides disorientation, I don’t know, it’s certainly not my intention. Mike certainly helps people listen to the instrumental content because a lot of people my age and older heard that voice all over MTV in the 1990s. He’s been sublimated, so I'm in this position where I can do whatever the fuck I want in the music and people are gonna listen to it because it’s him singing on it, so, you know, that’s a scenario where I go hard. It’s an opportunity to offer people another perspective, but I’m nothing, I’m just gonna end up fly food like everyone else. It’s not for me to say what’s natural or stable. How does the tabula rasa concept mirror your way as a composer use your senses as a way to navigate the world around you? It’s a process of forgetting. Xenakis talked about it. it’s a weird dual personality where you have to forget what you’ve done somehow, in order to be able to be free enough to do it again. You accumulate experiences and these influence your skills and perspective, but you can’t keep on doing the same thing over and over. Dependable artists don’t do that. As soon as the idiosyncrasy and immediacy is ironed out through repetition, you’re fucked. You need to listen to yourself in the present, where you’re at right now. The only way to keep renewing your practise is to somehow embrace and reject your experience at the same time. It’s completely weird but that for me at least is the only way I can continue to remain interested and engaged, to navigate the musical world freely. Many musicologists link the unique meters of Balkan music to the rhythm of the regional languages, specifically pointing to the poetry of Ancient Greece. Seeing as how your compositions are heavily influenced by your Balkan upbringing, do you feel that the time signatures used in this album mimic ancient poeticism? If so, how do these poetic parameters further create the tabula rasa soundscape we mentioned above? The Balkan thing is very much a technical influence and it’s something I’ll never be able to shake. Long sequences of 2s and 3s feel natural to me, and my father can’t clap in 4 but can do an 11 with ease. I grew up with that, and the politics of my family are complicated. My parents are from two tiny impoverished villages in the very north of modern-day Greece, right on the border with former Yugoslavia. This area used to be, under the Ottomans, classified under a broader region called Macedonia. After the Ottomans were toppled in the Balkan Wars 1913-14, the area was divided between multiple countries, most of it given to Greece, then some to Albania, Bulgaria, and a little bit left for the people who actually lived there. The bit that our villages fall in was in Greece, and when Metaxas came along, he embarked on a campaign of insidious and violent ethnic cleansing, mainly involving the hellenisation of all of the familial names and toponyms of the area. In some extreme cases, people who spoke Macedonian had their tongues cut out. As a result, our family has always been bilingual, not by choice. So you know, I’m conflicted about it all, what to call myself, ethnically speaking. Layer this with the experience of my grandfather immigrating to Australia after the second world war, and it just gets even more fucked up, because my parents did not teach me their languages, presumably to protect me from the racism and class discrimination in this country. And not only is Australia a nation founded on genocide, many people who’ve immigrated here have progressed that arrogance and hatred towards the very outsiders they once were. This is all to say, I don’t feel connected to any ancient civilisation, but I certainly feel a presence of trauma from 20th century Europe and the resulting post-colonial nightmare, inherited through my family, even though I’m a kid from the suburbs of Melbourne. Considering all of this right now, I don’t know if that’s what drives me to make the sound I do, but certainly I’m sensitive to how horrible humans can be and have witnessed the effects of colonialism first hand by virtue of being born in Australia. Do you have any favorite poets in general that have influenced your understanding of music? No. People are, typically, very poor at writing about music. Describing sound in text for me always falls short, and I’m not talking about the oft-cited music/writing -dancing/architecture axiom. I mean, let’s fucking dance! It is possible to have intelligent discourse about music, but so often it’s just people showing off their record collections and dropping names. Mark Fisher is a great exception to this, in that he sociologically and aesthetically addresses the impact of technology and the internet on sound. This is not (intelligently) addressed enough. It’s a weird paradox that with everything at everyone’s fingertips, people seem to know less. Hal Wilner dying of coronavirus is just a fucking tragedy. I mean, that kind of encyclopedic passion combined with musical integrity seems to be increasingly rare, but I believe it will come back. This nonsense we’re living is gonna stop, it has to. What I find more helpful than anything is reading the semiotext(e) stuff, especially the Chris Kraus novels, about the experience of being an artist. Putting it all on the table and pulling the mechanics of the ‘scene’ apart; its power-plays and problematic socio-political shenanigans, the kinds of personalities you have to deal with. It just comes as a relief to read someone be so articulate about it. Using personal experiences to talk about something bigger as opposed to self-indulgent navel-gazing is a helpful tool. You noted how this is the first album where you felt compelled to write more melodically and incorporate "attractive" melodies. What do you think caused this shift in your intention? And how does your love for 70s Brazilian music act as a guideline for what is "attractive" in music? (P.S. - I absolutely love the "Funerale Di Un Contadino" cover as the closing track.) I think it was something about realising there was a huge disconnect between what I was doing and what I actually enjoy listening to. I mean I talked before about shifting language; it’s really the only way to get through. I’m gonna do this till I die; I can’t be ‘the maniac pianist’ that whole time, I’ll get bored. My friends will too, you know? It’s about keeping the dialogue open, or as Donna Harraway puts it, ’staying with the trouble’. The trouble for me is that most people think that musically, all possible spaces have been filled. I believe, perhaps stupidly, that we shouldn’t abandon the abstract modernist sound project, but expand it into other territories such as rock music or beat/bass music or whatever. In its traditional form of the concert hall, one I’ve worked in quite a lot, there’s a glass ceiling. You can’t do anything there unless there’s someone up the food chain saying ‘this guy is alright’ and you can make a whole bunch of rich assholes get richer. I’m not into that. I wanna take those skills and transplant them into a forum where the people I’m working with and the audience are actually people I wanna hang out with and talk to afterwards. So, maybe that caused a shift in my intentions, plus, there are four main elements in music that every compositional decision addresses: duration, frequency, amplitude and timbre. Frequency can be shaped into melody. To shy away from melody all together is to negate possibility, and I just hadn’t done melody that much. Every new record for me is about learning how to do something I couldn’t previously do. So now I’m learning how to do melody, but I would never sit down and try to learn Brazilian music for example, because it would feel facile and insincere somehow. That said, the radicality in orchestration on those records from Caetano or Milton or the groove propositions from Vinicius de Moraes or Cartola certainly find their way into my technique through other means. It seems that you're no stranger to working remotely, so do you have any other projects you're working on during quarantine? Any distant plans for tētēma/anything else you'd like to add? In quarantine I’m taking the time to re-learn the piano in another way and take more time to write the music I’m writing. Normally I’m bouncing between Australia and Europe, writing pieces between tours, at an uncomfortable rate which needs to be maintained to make ends meet. It’s an absolute privilege to live off what I do, but it can be a stressful way to make a living, and it’s hard to find the time within that to develop things properly. Good music takes time! What I find a shame about this pandemic situation now, apart from the fact that loads of people are dying and everyone is scared, is that artists feel the need to keep producing throughout this. I view it as a productive opportunity to make what already you do even better, and/or take it deep in another direction. There’s no way I’m gonna watch a zoom concert with poor sound and visual latency. That is not what communication is about for me. Turn your computers and phones off and go into your practise room or studio and make something special. Come out the other end and share it with people, and not on the fucking internet!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Interview Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed