|

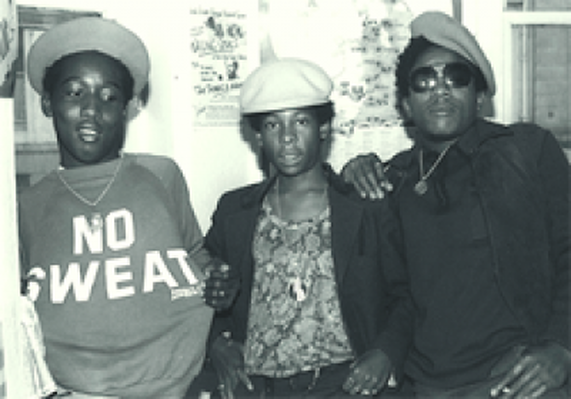

Written by Adam Iddings This piece is a classic coming-of-age tale of three Jamaican boys who would become three rapping young men. These were the children, Billy Boyo and Little John and Little Harry, that when they were just a couple of tikes waddling around on the boardwalk were scooped up by Toyan and Junjo Lawes and the Scientist. Beneath the palms shading an oceanside walk, perched above a pit of jagged rocks, you had Billy Boyo, Little John, and Little Harry moseying along in the middle of it, closing the gap between them and the on-moseying row of older role models. Junjo Lawes, Toyan, and a guy dubbed the Scientist. Waves splashed up the rocks at the lot of them, all six, and the three elders swore they’d school the boys. They told them, “Boys, if you can rap, we’ll be rich.” And that’s how the unassuming little rascals became the world’s first rapping Lil’-Young-anythings. Toyan himself was reasonably young, too, and he was a rapper. And when I say rapper like this I’m meaning the early rapping. Lots of repeating of things, especially your name, yet letting all things seemingly flow freely, remarking even in its repeating on how easy it is despite the toughness or roughness of life. Toyan was one of those rappers, a dancehall favorite, and he fixed it so that he could pass on his rapping prowess to his posterity. He scooped up those kids and had them grow up and become teenagers surrounded by reggae and rap of the newest, youngest style, the new DJ style, the rub a dub style, in a dancehall style, dancing on the dancefloor style, which the young kids would grow up to dominate. They would go on, these kids, to thank Toyan for the chance to grow up in his charge, his inspiring them, producing them. And then Junjo Lawes was just the producer; he was just the producer to do it, too. He was a young lad as well, only about 20 or so when he came out to the walk and encountered his most precious resources, those three kids. Even starting so young Lawes’s production discography is stunning; he must have been like a young Napoleon of musical conquests, overcoming in each release whatever strictures set by the precedents, himself becoming like a dancehall president in the process. So the list is like his presidential career, to be recorded someday in the Henry Junjo Lawes Presidential Library in Kingston, not to mention also being just a list of my favorite reggae records, bud--and their dubs. And so finally their dubs were done by none other than a character called the Scientist. He was also a young prodigy at making advancements for sonic-celestial space exploration; he was to reggae what Young Dr. Frankenstein was to Romanticism, a scary paragon of creativity. So these three were the de facto family members of these other three, the little rapping children: a young rapper, a Young Napoleon, and a Young Frankenstein taking three musical orphans under their wings, producing them, engineering them, building them up to be good rapping young men. The family bounded and boomed into success. The facts and the histories of the family have been recorded as singles, most of them self-aware missives on wanting to make it big rapping--a narrative we’ve since come to find very familiar, even more familiar than the family might make it seem. When they were doing it, it was new. These roots of the rap family tree looks like this: ★“What You Want to Be,” Billy Boyo and Little John: asking a serious question; ★“Wicked She Wicked,” Billy Boyo and Little Harry, Roots Radics band boyo, Junjo-produced, Scientist-engineered: a femme fatale tale for teens; ★“Janet Sinclair,” Billy Boyo and Little John, Roots Radics band, Scientist-engineered: when our heroes were in trouble and needed a maternal guide; ★“I Like Your Something,” Billy Boyo, Silver Kamel-produced, Toyan-helped: who wouldn’t like it?; ★“Bushmaster Connection,” Billy Boyo, Little John, and Toyan, Roots Radics band, Toyan-produced, Scientist-calibrated: speaking on violence in a youth-cultural slang--what a trope!; ★ “Rougher than Rough,” Billy Boyo, Little Harry, High Times band, Junjo-produced: self-explanatory; ★“Billy Boyo in the Area,” Billy Boyo of course, Roots Radics band, Junjo-produced: representing where the rapper’s from, proclaiming himself here not unlike his older, American contemporaries who were always “in full effect”; ★“Space,” Billy Boyo and also a little Little John, produced and engineered by Sinbad sailor of the seven seas and another early discoverer of the dancehall world: speculating on the afterlife; ★And “Jamaica Nice,” Billy Boyo: Jamaica-made. ★And in presenting them to you in this way I’m just meaning to share how I starred them soon after I listed them on my own. The effect is like painting a starry picture of a young man’s Jamaican nightshore, wandering on it as in a reggae bildungsroman. The production does that. The galactic genius that inspired the elder family members to use maracas and guiros, laser beeps and zaps, rocket flares, jungle hoots, snake slithers, aluminum warps, concrete claps, the whole discordant symphony of nature and man, the whole grab-bag of sounds--to use those is a genius borne of the nightshore’s beach. In Jamaica was this group of geniuses, a family of arrangers of flows flowing forever into their ebbs in dub. It’s really nice to listen to them, these singles. In them I hear man maturing in the universe. That’s to say nothing of the Billy Boyo and Little John and Little Harry story itself. Sure they had parents; I don’t know anything about their real parents, but I know that these three candy-faced kids on the boardwalk that one day, twelve years old, were soon rapping over the operatic and innovative productions of their adoptive uncles. Claiming adult dilemmas in rhyme. Shouting “Murder!” and “Ribbit!” over the album’s dub. They had turned themselves over to that other side, the adult side, the dub side; their crystal-sugar faces had cracked and created something brilliant. Through those cracked facets they could rap their Dickensian stories. Getting picked up by uncles and made to inherit some money. Fulfilling their great expectations with the aid of their benefactors. Discussing society’s ills and how to get by in spite of them. They brag, these kids, about their pick-up statistics, about the ways they pick up girls, their status as picked on, as tougher and rougher than rough, repeating themselves, resolving themselves to be what they want and were wanted to be. Billy Boyo says he’s super-duper. Little John says he wants to be a disc-jockey. A few hundred years ago, it was always boys singing. There were these boys’ choirs that sprang up during the Renaissance that would put on short little plays and do high-voiced choral performances. It is a tradition that spans centuries, generations, hemispheres. So in the early 1980s these Jamaican youngsters took the proverbial torch. It was not long before they put the torch to use that they made themselves stars. The boys’ choirs of old performed in cathedrals; these rapping children of Jamaica performed in dancehalls. These respective environments afforded similar tones, too--not just the soprano lilts of their boys’ voices, but also the hard echo, the hollow resonance of their walls. The church hall is a concert hall is a dancehall. And in entering that hall these boys entered also a hall of fame of rap, is what I want to say. Just that; listen to these kids, man, and appreciate the incipience of hip-hop and especially young hip-hop in their tiny-timbred bars about murder, music, and prospective manhood. What do we hear, when we hear the Lil’ Waynes and Young Thugs and Yung Leans of the world, but the roots of young rap in these reggae child stars.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

PLEASE NOTE: For the first two weeks of May, we will be revamping our blog sections and moving posts so that the site will be easier to navigate. Please pardon our (virtual) dust as we shift things around. Thank you!

World and Jazz Archives

June 2016

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed