|

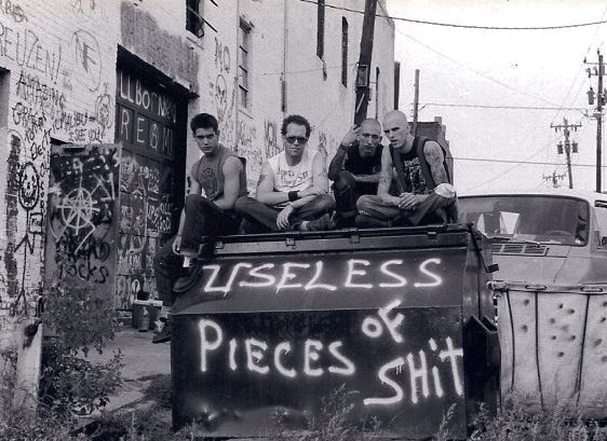

Written by Greg Gonzales & Parisa Eshrati Tucson's not traditionally known for its 1980s hardcore punk scene, but it should be. Bands and fans gathered from all over the desert Southwest to participate and revel in truly original music. This piece uncovers the artists that made up Tucson's early punk scene and discusses their influence in Southern AZ's music culture today. Mohawks, liberty spikes, shiny bleach-blonde locks, and hot pink highlights swing above a moshing throng of punks in downtown Tucson, in the middle of the intersection at Congress and Stone. The leather's hot in the air, and you can smell it if you think hard enough. The MC announces that Useless Pieces of Shit (U.P.S.) are about to play. No cars. No streetcar. It's late October, 1984, and one of Tucson's own punk bands is playing live, blasting original Tucson music into the desert air. But how did Tucson come to put on a punk show in the middle of the street, and where did everyone go from there? That night probably started five years earlier, in 1979, when punk bands started to pop up around Tucson. At that time, bands like Suspects, Z-9, and The Pedestrians ruled the scene, and served as a catalyst for the years to come. “The Pedestrians and The Serfers were two of the first punk/new wave bands doing stuff like Ramones, Stooges, Devo, Talking Heads covers, along with sixties staples at places like Record Room, Pearl's Hurricane, The Night Train, and Tumbleweeds during the tail end of the 70s,” said Mark Beef, Tucson musician and guitarist for Lenguas Largas. Other bands gave their punk a different image, though perhaps more familiar. “Civil Death (which would later turn into U.P.S. when members merged with members of Corporate Whores) and Conflict were two of the first to really kick it up a notch,” Beef said. “U.P.S. used to tour pretty regularly and, if nothing else, were a big part of making tattoos be an honored tradition of the punk world. They were one of the first to have pretty heavily-tattooed members.” By the mid-eighties, the scene found definition, calling itself THC, for Tucson Hard Core. Lineups changed as earlier incarnations formed new bands, and new sounds emerged. According to Gene Armstrong, host of the Roadshow on 91.3 KXCI, The Serfers played “dark, keyboard-driven punk. Played many a great show,” which he says includes an early gig at Tumbleweeds that set the parameters of what Tucson punk and Tucson's punk audience were. Later, the band would be included in the Paisley Underground psychedelic revival. The Pills, Armstrong explained, were “excellent, kinda snotty, New York Dolls-style punk-pop, with one remarkable four-song EP to its credit.” He added that he regretted a poor review of their later incarnation, as Gentlemen Afterdark, which released an EP produced by Alice Cooper. A more familiar name might be Giant Sandworms, the “earliest Tucson version of Howe Gelb's eclectic vision,” Armstrong said. “Made a terrific seven-inch EP with Rainer Ptacek, David Seger, and Billy Sedlmayr.” The band reformed as Giant Sand in the mid-eighties, and still influences Tucson music. Armstrong also noted Phantom Limbs for their danceable new wave pop, and bands like The Hecklers, Jonny Sevin, Bloodspasm, Feast Upon Cactus Thorns, and Opinion Zero. “There are way more than I mention here,” he said. Other Tucson bands that contributed greatly (and everyone should go listen to) include White Pages, Memory Product, and Al Perry & the Cattle. By 1985, purists might say, Tucson's scene peaked — Al Perry and U.P.S. opened for Dead Kennedys, which some fans saw as affirmation that Tucson was officially on the punk map. Al Perry himself noted that Tucson was something different because of its isolation. “It's a small town. It is not a music town,” he said. “That allows the bands to develop organically. No one much cares about pleasing any sort of music industry. Therefore, the bands are more unique and interesting.” Bill Sassenberger of Toxic Ranch Records echoed Perry's sentiments: “I remember talking about Tucson punk with a friend in Phoenix and he said you could always tell the difference [between Tucson and Phoenix punks] because punks from Tucson were the unclean ones dressed in rags,” he said. “They weren't freshly scrubbed as the more affluent kids in the valley.” Punk in the desert really has to be something different. The genre itself is steeped in rage, whether socially or politically — and that kind of discontent is everywhere, even out in the desert. “As it did throughout the country, the Reagan presidency helped inspire the rise of American punk rock — to provide an opposing voice for youth, of course,” said Armstrong. “The heat of the desert, too, has been an inspiration. Sometimes this because of the hallucinogenic qualities the high temperatures bring to an overheated brain and imagination. But also — as the guys from J.F.A. whimsically said in a long-ago interview — you can’t drive away from the desert on retread tires because they disintegrate on the hot asphalt of the highway. So you’re stuck here.” When music evolves in one place, it acts as a kind of sealed cesspool, like that cave in Romania where creatures evolved in dark isolation for 5.5 million years, adapting to a world quite different from our own, becoming something very different themselves. In Tucson in the mid-eighties, according to Armstrong, some of the bands began to move away from dictionary-definition punk and into other genres, while other bands adopted “the more aggressive strains of hard core punk filtering down to us from the big cities.” That degree of separation helped set Tucson apart from the rest of the map. Armstrong said Tucson's punk bands were less restricted, that they were less concerned with fitting the textbook punk or hard core sound. “They often incorporated pop, country, psychedelia, blues, avant-garde, and rockabilly into their interpretations of what punk could be. …. The punk scene in Tucson was different from that of Phoenix or the rest of the state (and the world) because it reflected the unique Tucson sensibility: a little more left-leaning, a little more home-grown, somewhat artsy, willing to give up luxuries for your art, being defiantly DIY (which includes not depending on others to do and make stuff), the support of all musicians and artists for each other. I think the above qualities define Tucson arts in general, including punk rock.” Punk’s popularity in Tucson also depended on smaller influences, more in number. According to Beef, Paul Young of bands Civil Death, U.P.S, and Blood Spasm turned kids on to badass underground punk through his job at Zip’s record store. Young would order the punk records, and show unsuspecting kids who were searching for mainstream records the raw power of the Old Pueblo and beyond. Some of the skate and head shops carried punk records, too, while Toxic Ranch provided the bulk. And though it doesn’t seem significant, Toxic Ranch sold books and movies and other items from labels that otherwise couldn’t exist in Tucson. That’s where fans could really dig in. Those bastions of information and devilish whispers of forbidden tunes are crucial to shared discovery within a scene — people come together over music — and the social discourse, the friends and connections, are just as important as the music itself. Despite the fervor and love among its fans, Tucson punk wasn’t greeted by the community with open arms, freedom, and classic venues. Punk-friendly venues often lasted mere months, even though they found great success while open. Wrex Club by Chris Olivas and friends was an all-ages club that didn’t serve alcohol — that was the story for a lot of punk clubs, since many of the fans and members were underage — but the venue closed after three months of being open in winter of 1985. “They feel threatened by it,” said Olivas in an interview about Tucson punk clubs closing. “When you have the punk scene and the people — they’re not any more aggressive than the other scene, except for maybe on the dance floor, and usually [The Man] doesn’t like it, so they use it to close the clubs down.”When asked a similar question in the same documentary on YouTube, about how the scene is perceived, members of TSOL, MIA, and Don’t No Bands summed things up with some slightly tongue-in-cheek explanations. “Rock ‘n’ roll was always meant to be frightening,” one member said. “When mom and dad in the fifties saw Elvis, they got frightened. Then The Beatles came out, and the Stones, and they were frightened in the sixties. And now it’s us and MIA in the eighties.” “For people who don’t understand it, you gotta relate it to tackle football,” another member explained. “It’s not like you’re out there hurting anybody, or hurting your buddies. It’s part of the game.” Like any misunderstood game, though, punk needed someone to defend and honor it. That champion came in the form of Steve Eye, owner of Solar Culture Gallery downtown. Steve Eye was a Philadelphia skateboarder, who built Philly's first quarter pipe and brought the city's DIY mentality to Tucson. “In 1980 we first heard about American hard core Punk Rock from one of the pro Cali skaters that had come to do a demo at the skatepark,” Eye said. “Shortly after that, the insurance industry raised the insurance rates on all of the skateparks all over the country, and most of them closed down, spawning the beginning of punk rock DIY culture in almost every city across the country.” By '83, the Philly scene peaked and he set his sights Westward, to Tucson. “After two years of idyllic life in Tucson, I was missing the city life, and was ready to make some punk rock energy happen again and in '87 rented the warehouse at 31 E. Toole,” a place called Hellrad Club, which then became Dodajk Internation, which hosted the likes of Fugazi, NOFX, SNFU, Helios Creed, and Tragic Mulatto. However, the police weren't huge fans of punk or its audience, and harassed Eye into no longer doing shows. Despite swearing to never do a show again, Eye found motivation through support from the scene, and founded Downtown Performance Center in 1991 — an even more successful venue. Punk couldn't have thrived in Tucson without Eye's venues and support, but the scene was still a fight the whole way. When the crowds had no place to go, they took punk to house parties, the Unitarian Universalist Church, the Bridge Center, and warehouses in and around town. However, as punk grew into an accepted nationwide and worldwide movement in music, and Downtown Performance Center opened, the scene exploded into something bigger. Even headliner acts like The Offspring, Ani DiFranco, Stereolab, and Bad Religion played the DPC. Punk could no longer be pushed aside by the mid-nineties. The scene bled into neighboring towns, where even more bands had a hand in the scene. Vic Morrow’s Head played a role in Tucson from as far as Yuma; from both sides of the border, you had Democracia Real, La Merma, Swingding Amigos, and Acho; and American Deathtrip. Malignus Youth, from Sierra Vista, added their more technical, classical stylings to the mix. The band got quite a following in Tucson, despite living more than an hour away. “Sierra Vista had its bar bands, and if you were playing ‘Breaking the Law’ on the bass with more than one finger, you were Mozart,” said Malignus Youth drummer Mike Armenta. He credits Dover Trench, a band from neighboring Cochise County, for starting the punk rock scene there. “Not only could they play ‘Seek and Destroy,’ Dover Trench was far and beyond musically brilliant with downright complex compositions of their very own that rivaled Slayer,” said Armenta. The band later played with Slayer in 1991. Tucson and the surrounding areas were and still are filled to the brim with talent like Dover Trench. By the mid-nineties, Tucson deviated from having a directly hard core punk scene, though the raw spirit remained very much alive. The eclectic experimental ensemble Brenda’s Never Been, for example, wouldn’t be classified as “punk” music, but their avant-garde stylings and DIY ethic carried on the legacy that was evident in the music scene years before. Similarly, Mondo Guano was a genre-less four-piece band that maintained the weirdo, distinctly-Tucson punk attitude. The group consisted of Bob Log III on a hallow body slide guitar, Montaigne Benoit on a fretless bass, Danny Walker on make-shift drumset generally made up of buckets and crates, and vocalist Nicole Pagliaro whose alluring voice would seamlessly cut through all the noise and muffled feedback. Armstrong recalled a note Tucson musician Bob Log III wrote to him about Mondo Guano: “Like a home-made pie versus a Twinkie: not` perfectly shaped, maybe with a bit of filling oozing out, and possibly a little burnt on the edges, but way more delicious and real.” The whole of Tucson’s music scene at that time wasn’t far off. Steaming, sweet, scrumptious authenticity — with burnt edges to keep it rooted in that raw punk energy. Bob Log III went on to create Doo Rag, a blues-punk group that played with Sonic Youth, Beck, and even toured with R.L. Burnside. Though many of the bands from Tucson’s premiere punk days never received the proper attention they deserved outside of the state, their legacy is apparent in the eagerness and fight that Tucson’s music scene observes today. Just like in the early days, venues in downtown Tucson have been closing down left and right throughout the past several years. The District Tavern, one of downtown’s beloved watering holes and host of countless cover-free punk shows, have been replaced the likes of Hi-Fi, a bar where you can listen to DJs playing the same “90s Dance Hits!” playlists while you watch a football game on one of their 600 televisions. That doesn’t mean Tucson has handed over the music scene to the college crowd, however. David Rodgers, one of the co-founders of Southwest Terror Fest, notes, “We can't even begin to bounce back yet [from gentrification] because we still haven't bottomed out on losing venues and resources. When you lose venues, support, all of that....it affects everything from the top to the bottom. That said, nothing will ever kill music in Tucson. They might make it harder, but it's a musical town and it will continue to flourish one way or another. Amazing bands are coming out of Tucson every year still.” It’s still yet to be said what the punk scene in Arizona will be like for the next generation. Whether or not Tucson conjures up a full-blown scene for hard core music again, the influence remains an absolute certainty. Tucson's music legends are today's leaders, like how music vet Cathy Rivers now runs KXCI, members of Mondo Guano rock us in The Pork Torta, and Steve Eye's Solar Culture still gives a stage to bands that might otherwise not be able to find one. The music scene isn't going anywhere. “As long as kids in Tucson feel like outsiders from society at large…and are more interested in expressing themselves through music/noise than they are in having ideas dictated to them…[punk] will exist,” Beef added. “As far as the future, that all depends on how this generation prefers to be remembered by the next one,” said Sassenberger. “The cycle continues.” And the beat goes on. --- Special thanks to Mark Beef, Gene Armstrong, Bill Sassenberger, Al Perry, Steve Eye, and Cathy Rivers for letting us pick their brains and preserving Tucson’s amazing music culture.

For related reading, check out our interview with Sierra Vista hardcore group Malignus Youth about the early punk AZ scene here.

2 Comments

Defendthewest

3/16/2021 12:11:28 pm

Good.

Reply

I thought I would hate this, but it gets some things right. For instance, being in a town with only one Interstate, one rail line, no intersections... the remoteness of Tucson really did encourage a special creativity. We were playing for each other, not for some imagined record company guy in the back of the room. Later, I moved to NYC, and played in some small clubs there, where all the bands were recent college graduates trying to become indie rock stars. Compared to the creativity of the Tucson scene, the NYC club scene in the 90s sucked.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Blog Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed