|

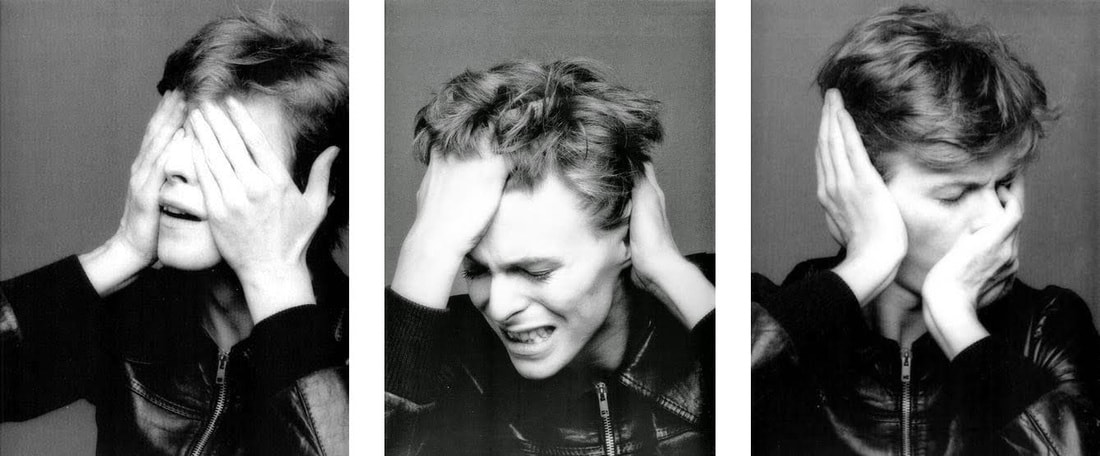

Written by Hannah Hollins David Bowie's personas of the seventies were his vehicle for access to different cultures: they legitimized his presence in those cultures but also allowed him to comment on them from an outsider’s perspective. Independent of his personas, he continued to expand to new forms of expression through his astute collaborations and experimentations with bending musical genres. This piece is a retrospective of the evolution, progression, and influence of David Bowie’s creative work in the seventies and today. David Bowie was a cultural and musical embodiment of reinvention. His artistic influence was widespread not just because he was constantly changing,* but because he was very good at changing. He had the foresight to remain atop the crest of popular culture and the finesse to simultaneously embrace and critique the cultures presented by his persona du jour. Outside of his personas, Bowie’s astute and relevant collaborations continued his expansion to new planes of experimentation in musical genre and narrative. During his time on Earth, he was viewed a visionary; as we regard his work in retrospect, he is a historian. At a surface level, Bowie's evolving personas were the most visible ch-ch-change to the public eye. Bowie busted into the seventies as the dress-wearing longhaired blonde who Sold the World, he was then Ziggy Stardust, Halloween Jack (“Eyepatch Bowie”), the Thin White Duke, and then he was through with personas, off the cocaine, and living in isolation in Berlin. These personas of the seventies were his vehicle for access to different cultures: they legitimized his presence in those cultures but also allowed him to comment on them from an outsider’s perspective. Ziggy Stardust, intergalactic rock star, touches down to Earth and reaches out to the world’s young, electric people with heavy glam rock that expounds observations of fear and sex and otherness. Early on in The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust, an older generation mourns their own degradation; the power of “Soul Love” is transferred into the rising young generation’s hands. That power is manifested in rebellion— the younger generation’s optimistic defiance pushes back on their parents’ values as they plan to sneak out and sparkle for a Starman, to “use it... [and] lose it,” because they are not afraid of his message (“Starman”). To mark that schism in sonic terms: the folky acoustic foundation in the album's beginning tracks loses its dominance and gives way to Ziggy’s commanding voice, the swooping and screaming electric guitar, and the slinky energy of the Spiders from Mars. Once Ziggy the Starman gets onstage, his anxiety about fame and desire to please everyone shines through the groove and sparkles in an unquestionably dark and sexual energy (see especially “Moonage Daydream” and “Lady Stardust”). However, touting the dangers of glam bite Ziggy in the end— he “sucked up into his mind” (“Ziggy Stardust”) and burns out in a flame of sex and rock ’n’ roll, reverts to his humble acoustic beginnings, and strangely, plays out his end with an orchestral arrangement of elegant strings (“Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide”). The raw sexual energy of Ziggy Stardust spirals into chaos for Ziggy’s vampy American cousin, Aladdin Sane. He is invited to the hippest parties in New York City— ones where he isn’t the center of attention (“Watch that Man”)**— and the scene makes him so nervous that he “[runs] to the street, looking for information.” Whether that is word on what’s hip, context from somebody in tune with the news, or maybe a quiet place to think, the rest of the tracks on Aladdin Sane capture the belligerence of American Citizens. This rock album is anchored on a foundation of pounding piano keys that occasionally twinkle and arpeggiate to make a point, crunchy and wailing electric guitars, and rogue jazzy saxophone riffs. Aladdin Sane, refusing to be swallowed by the intense music, emotes his message through profound and desperate lilts. Aladdin Sane pushes towards the vaudevillian while retaining the glam edge from Ziggy Stardust. In America's late seventies, energy was still buzzing from the sixties’ mindless conscription and drafting to wars abroad (“Aladdin Sane”) and ‘wars’ domestic to America, notably race riots (“Panic in Detroit”). Aladdin Speaks relates and speaks directly to the Americans tense and weary from the violence, vacuity, and excess of the era: “You are not a victim/You just scream with boredom/You are not evicting time” on “Time.” But, in order to carry on, Aladdin Sane ultimately finds his groove in the bop-bop power beat of American aggression (“Let’s Spend the Night Together,” “Jean Genie”). Station to Station embodies the manic frenzy of a self-loathing monster of a man— the Thin White Duke— who turns inward and can only define the world around him through a series of desperate attempts to apply human interaction, religion, and philosophy. He is different from Bowie’s other personas because he does not attempt to critique a culture or address an audience, but his music is an open invitation to spectate his self-loathing. On the ten-minute title track, “Station to Station,” the Thin White Duke is caught “throwing darts in lovers’ eyes” in his jealous search for clarity and love amidst existential crisis. Pianos and drums pound with a darker percussion, echoing through a vacuous space, and a tempo change whips the rock into a hammering, manic groove. The sound of Station to Station is rooted in the funk and soul of his previous album, Young Americans, yet it pushes onward into the electronic synth waves and drums. At the bottom of his spiral, there’s no stable relationship, and there’s no friend to prop him up and say, “this time I know we could get it together” (“Stay”). The end of the Thin White Duke marks the end of Bowie’s era of personas. Bowie himself had grown desperate, serious, and soulless, and he floats the idea of confronting himself through the Thin White Duke’s soulful crooning and groovy beats. In “Word on a Wing,” the Duke predicts that he is “ready to shape the scheme of things”-- and so Bowie split America without pomp and fled to Berlin to explore expression and experimentation through isolation and instrumentation. Bowie’s personas teach his listeners much about how to be genuine while pushing a temporary or permanent agenda. In other words, a form of expression is legitimate as long as it is rooted in truth— your inner truth (however you perceive it) should dictate how you express yourself, and not the other way around. David Bowie was unabashedly other, and he acted this out in terms the public could understand by dressing, performing, and acting in a series of daring personas. At the core of every persona was the observer (David Bowie, the artist***) with something to say about the world around him, and/or something to say about himself. As a result, the public’s perception of culture, reality, and “normality” was expanded when they participated by listening to his music and watching his performances.**** Low, Bowie's first post-persona album, is a testament to his persistent foresight and creative lizardry— that is, he grows a new musical tail after having completely severed his own identity from his personas. On Low, Bowie expresses himself through soundscapes that evoke his anonymity and disassociation while living in West Berlin. The mood of Low rests on Brian Eno’s synth-driven musical direction and Tony Visconti’s production of the electronic beats and ambiance. The result is an album with a remarkably futuristic sound and a narrative that reflects Bowie’s struggles to escape his own cyclical, destructive behaviors. “Speed of Life,” Low’s opening instrumental, guides the listener through a melody that changes often, reprises occasionally, but stays on the same beat. It’s a chugging forward, or a spiraling outward. In the track “Sound and Vision,” Bowie sheds light on the frustration of his new experimentation. Low is a quiet record, narratively speaking, because Bowie is desperately stuttering to share a message of isolation and desperation without the prop of a persona. Refusing to acknowledge his stunted creativity, he declares, “I will sit right down, waiting for the gift of sound and vision.” Despite the lack of a cohesive lyrical narrative on Low, what holds it together is the duality of its arrangement: side one is comprised of short songs— developed fragments, really— that echo “Speed of Life,” and side two is a series of slowly developing, instrumental, moods. Low and the other albums of the Berlin Trilogy***** are David Bowie’s first step into the avant garde; Low is also the point where he sloughs off his hitch with personas and begins to claim his cultural observations, his lyrics, and his music as his own. Outside his work with Eno on the Berlin Trilogy, it should be noted that some of Bowie’s largest musical successes in capturing and bending genres have come from collaborations with experts in those particular sounds. Luther Vandross had significant input in the R&B and soul sound on tracks of Young Americans. Nile Rodgers’ co-production and Stevie Ray Vaughan’s guitar contributions resulted in several successful singles on Bowie’s post-disco banger Let’s Dance, which cut so cleanly to the heights of popular music in the early eighties. While his level of involvement in cultivating a certain sound varied (compare Brian Eno’s pretty much independent creation of “Warzawa” on Low to Nile Rodgers’ addition of a hook to “China Girl” on Let’s Dance), it was Bowie’s motivation to spark these collaborations, and it was ultimately Bowie’s vision that appeared on each record. On 8 January 2016, Blackstar was released on David Bowie’s 69th birthday. Considering his life’s work, Bowie transports his audience from rock to glam to soul and funk to dance to electronic and back to rock-- he is a nitrous mass of creative influence that trickles to new lengths and refuses to simply be contained by one genre. Blackstar is a new musical evolution for Bowie: he directs a blended avant garde jazz that incorporates most of the sounds from his previous work, plus a little hip hop. In recent years, electronica and hip hop have tilted heavier than rock on the scales of popular music. The music of Blackstar begs the question, what’s the next evolution of pop culture’s sound? Three days after the release of Blackstar, David Bowie died. But in the narrative of his final album, he gives his audience a parting present of one last persona: David Bowie as a Lazarus figure. The Blackstar tracks that reflect on Bowie’s personal experiences are relative to his position in life and also to his position in death. That thematic duality is echoed in the story of Lazarus, a man who is brought back to life after death. Blackstar is also a reversal: a star usually shines bright, but this inverted star radiates darkness.****** In life, Bowie’s persona is the dead man; in death, his persona is the man who is alive. Look up here, I’m in heaven I’ve got scars that can’t be seen I’ve got drama, can’t be stolen Everybody knows me now -- “Lazarus” Bowie’s living “heaven” is his age and celebrated status as an artist with a history of successful musical experimentation; “everybody” knows him through his famous works, but he still withholds some secrets (namely, cancer). In death, “Lazarus” is played over a speaker, Bowie is resurrected and is speaking with his own voice from beyond. Though he’s dead, he is still haunted by certain parts of his life (scars and drama); and “everybody knows [him] now” because of the intriguing uncanniness that now floats around his release of Blackstar. This is creative foresight on a completely different level: Bowie has evolved from life into a new plane of existence, and he uses his music and narrative to send us a message that is genuine and relevant to his past life as well as his presence after death. Blackstar is a disruptive record in every sense. David Bowie, the master of musical changes-- and also the master of performance-- has executed an exit so in line with his creative vision that we’ve been rattled for days. Now when we play Blackstar, or spin any David Bowie record, he’s speaking to us from the past but his voice is very much alive in the moment. His works snapshot visions of the past that will be shared with and discovered by future generations. In a perpetually changing world, David Bowie will remain relevant, because his presence straddles his own past, his audience’s present, and the future of his legacy. ------ Footnotes * So did the Velvet Underground, so did the Beatles. ** The man in question is David Johansen of the New York Dolls. *** Or David Jones, the artist known as David Bowie, if it is necessary to go deeper. The argument can be made that David Bowie is the performative persona of David Jones. **** I’m too young to comment on the public’s perception of Bowie as this music was being released, but as a person who had his entire back catalog available since her teenage years, I can say the following. I’m a loud person with rapidly evolving style and a propensity to explore new facets of culture (music, lifestyles, hobbies) in my free time. The only thing about me that seems to stay the same is my inability to be calm or indifferent to something. I’m not uncomfortable in unfamiliar spaces, and I’m not silent when I’m confused. And I owe this learned confidence and curiosity to Bowie’s personas and post-persona musical experimentation. In my teen years, when I wrenched the autonomy to experiment from my parents’ wary hands, I conducted most of my changes with his records spinning in the background. Internalizing his art, I learned to not give a fuck about the public’s perception of my self-expression, because I could only feel comfortable when I was behaving in a way that reflected me genuinely. I sought out the unfamiliar and I did so as the theatrical nazz in sparkly, thrifted clothing. I embraced the fluidity of gender, power of sexuality, and my androgyny that confuses so many new acquaintances. Now (I think) I’ve watered down to more of a Berlin Trilogy level of subtlety. But maybe not. I’m always changing to something new. ***** Low, Heroes, and Lodger constitute the Berlin Trilogy. ****** The definition and intention of the word “Blackstar,” a title he gives himself in the album’s eponymous track, is still hotly debated. My interpretation is logical but not definitive.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Blog Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed