|

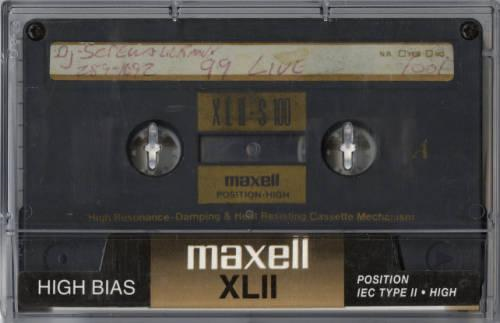

Written by Alan Kiddings To kind of quote one of the Psalms, Screw's tapes restore his soul. We shall not want, for he is with us. So watch your Screw, and I'll just say a few words of appreciation. I Making a tape, you record wavy marks of magnetism on some celluloid. The recording’s an electrical pulse that causes fluxes in the magnetism, and what results is the marks on the tape. It might be thought of as a pulse, as a pulsating on polyester film. So you’ve got your pulse, you know, and that’s like an impulse. Then if you were wanting to make a live tape of your pulse, had an impulse to record it and mark it down, your being alive, you’d transduce that pulse onto a tape; it’d mark it. And what you’d be doing is screwing electricity into magnetic waves. And that right there is what makes for a great phenomenon with the tapes of DJ Screw, where people want to mark him. Mark down the tapes. Mark the numbers of them. Tally ‘em up with markings. Cuz there’s a big archive of Screw, and Screw, with his tapes, make a big archive of rap. So if you want to see good taste, mark Screw’s tapes. Scope them, in their daunting scope, and mark them on a steno pad. Make the files for them. Record the contents of the files, so that you can hear them—that is, so that you can hear the recording of Screw’s Screw tape recordings, which is what I’m trying to do here, write a requiem recording. There are over 300 Screw tapes out there for you to find and file; stockpile them for the future from which “Hundreds more could emerge,” according to a fellow filer. Lance Scott Walker, this filer, adds a qualifier, writing, “[T]here are no ‘new’ Screwtapes. The genre may live with his name, but as every Screwed-Up affiliated person will tell you: it wasn’t ‘screwed’ if it didn’t go through his hands.” And I’ve added those italics to that to invoke the examples of others who’ve written about such marks. Archival work is all about such an invocation. Requiem-writing is all about invoking the written life, the marked life. These marks tape-make maladies in us, any of us who wanna trace what Screw touched, feel the prints of what went through his hands. After it went through his hands, it went on the tape. So the prints, the traces, the marks of those hands that screw could use to tell us what about that tape. They are the tapes; aren’t they the tapes that printed. With fingerprints on ‘em, tracing Screw’s life, the chopped and screwed life as marked, remembered and written in a chopped and screwed requiem, or as another marker partner who’s written about those print-traces writes, “It [that is, Screw’s hands through which the tapes went, the technology of his tape-making] conditions not only the form or the structure that prints, but the printed content of the printing: the pressure of the printing, the impression….” These impressions determine the moments appropriate to their being recorded, printed, traced, marked. When we consult the catalog, we are overcome with a fever to figure ‘em all out, to order and comprehend them for futurity. And like when Lance wrote, “[T]here are no ‘new’ Screwtapes,” he meant that any future Screwtapes will have been recorded in the past, in a past that passes over us as archivists. So in this requiem nothing will be new except what’s past, so that we might not have to hear Screw from his afterlife only, so that the past is more future than the future. As our marker partner puts it, “As much as and more than a thing of the past, before such a thing, the archive should call into question the coming of the future.” This requiem is borne of a keenness for that calling. I heard the tape and I had a drive — an archive drive, a drive to to say something to save something from being gone. “There would be no archive desire,” no drive to archive, “without the possibility of a forgetfulness.” Death is the thing of the past that sparks the flame of the fever for the archive; it’s the dark, behind the drive to archive. So I’m archiving here; I’m giving in to the drive, and writing, marking these words down, to stave off the end. I wanna write around to bring back Screw from the dead, so that he can be around, so that he can be back around again — a cassette spool, with a tape taped to it, rolling, screwing up more marks in the tape, making Screw tapes, chopping and screwing the tape and so the writing of the tape. When Mozart wrote his Requiem he wanted it to evoke the dead with its music. There have been before requiems for Screw, too. His archive is a requiem. The marker is a Mozart, is me. So if I’m gonna write any requiem right by Screw, invoking or evoking Screw, it’s gotta be screwed. How do I do it like Screw? Which is right there one more testament to Screw’s memory, that right there, cuz that’s the same question everybody in Houston is asking themselves in the early 90s, “How do I do it like Screw,” the question itself repeated and slowed to a chop and a screw. How? In the words of Screw’s close confidant, “Don’t say E.S.G. didn’t warn ya. II So watch your Screw. It’s dark, and it could disappear. Everything already sounds beyond the grave, above the Earth. There are tinny echoes deep down in the creviceways of my brain. What my brain is getting the sounds of, the stuff of, is DJ Screw’s 3 N the Mornin’ Part Two running through there right now. A Screw tape. It comes down from a thundercloud. Screwed. Then there’s the hiccups in the stories that are being told. Chopped. (And all this time I’m writing wondering, “How would it change a kid’s life, how would it blow his mind, if he’s a farm kid in Texas and he gets his hands on a Screw tape from some macabre monster that lives in the cornfields. A skeletal scarecrow hand reaching out from the tall stalks: 3 N the Mornin’ Part Two. And he goes home and sticks it in his daddy’s Ford’s tape deck. Then what? Do they tell the authorities that they’ve been beamed up by UFOs? Or do they mellow out? Do they call it “beamed and mellowed”?) Do they call it “chopped and screwed”? Cuz its provenance is dark, there’s a dark cloud over its echoes and all, so that it’s hard to see them, hard to hear how they’re called. III Cuz Screw would do stuff like chop the jokes from a Richard Pryor comedy record into an Outkast instrumental. He would go way back to songs he’d heard his parents play, like a lot of DJs. He had one song, “Don’t Stop the Music” by Yarbrough and Peoples. He’d chop and screw that disco-era jam when he was a 23-year-old fresh face. Youngster as he was, he heard something in the song that kept him going. Kept him going back to it. Back to it. Its message slow and clear: don’t stop the music. Keep it going back. Just because it’s two in the morning. Don’t you feel like dancing? Cuz Screw would play his tapes at parties, songs like “Don’t Stop the Music” to say just cuz it’s two o’clock don’t mean that we have to stop. These were party tapes, a lot of ‘em, party tapes made for being danced to. Rappers and friends would request to Screw, write him little letters on the back of napkins and shit: Dear Screw, please chop up “Reality”; please screw up “That’s What I’m Looking For.” And Screw’d put it through his system, then they’d get all that back on tape. Then they’d take that tape to their own party and they’d try not to stop it, not to screw it up, keep the Screw tape playing. Playing Screw’s tapes at parties. Playing Screw tapes at their parties. So here was this song, from 1978, DJ Screw is seven years old and here is this song he hears his parents playing. There was an idea then that poofed into Screw’s brain: “I could be the one that makes sure the music never stops. When the music stops, you know, like when the tape runs out or the record’s all the way spiraled in, it stops. And then people start to stand around with their arms folded and they’re just wanting to hear some more music. They wanna bring it back. So I could be the one to do that. Just keep the music playing. I could be a DJ. And I would DJ everything really slow. To not stop the music. For longer.” Not sixteen years later he’s a sound success, got all kinds of people lining up on the sidewalks out in front of his house and around the corner for him. Southside Houston wants the work that he’s put together, the art that he’s crafted, the tapes. The screwed tapes. The ones that would be played at parties. And it’s in that next moment, then, in his history that he goes back to Yarbrough and Peoples. He goes back and he chops and screws that song that (just speculating, now) gave him the idea to chop and screw. Four years after that, at the still-tender age of 27, he uses the “Don’t Stop the Music” muse another time. It’s for Fat Pat’s “Tops Drop.” See cuz you gotta imagine Fat Pat, the flyest man in Hollywood Houston—“Fat Pat” who “was everything” for Lil’ Keke, another of Screw’s confidants. Imagine Fat Pat swaggering over to Screw’s house, trying to get his bark onto the track, smoking a blunt the size of a steak, saying on Wineberry Over Gold, “Man I’m throwed man it ain’t no mood, man…. This real,” and then sailing into a beatific-quotidian freestyle of a regular guy, who happens to be able to rap, about his regular-ness, and who you could probably watch sports with, whoever you are, swagger-less as you might be. Probably have a shared knowledge with, with him. Have at least similar tastes to, to you. And he sails and sails and sails for ten minutes completely enhazed on his mceeing on his ennui. On his same dreams as you. On his same dreams as you, you and Fat Pat, whose ghost would release an album, who would release a ghost album, called Ghetto Dreams. Imagine him in that ivory white suit in your dreams. This is Fat Pat. This is Fat Pat. This is Fat Pat in Paradise. French doors open up and everything and there’s a glow behind him. Y’all shake hands. Pools of clouds. Water spilling, water spilling over cloud bathtubs, cascading from cloud fountains in the corners of the living room, setting the mood, making the throw, throwing in the game, blowing out the frame, living in that dream, knowing what I mean. He’s wearing gold chains and gold bracelets with his name etched in ‘em. He asks me if I want some of that slow-making lemonade or some Sprite or something. And then he sits me down, grabs the drink, and orders some wings. “It’s all good,” is how another Fat Pat tape begins, thundering from the clouds. “I’m telling you; it’s goin’ down. Fuck the media. Fat Pat is here.” Yeah man let it be about this tape! The Fat Pat tape! Let it be about Fat Pat and his life, his days, his birthdays. Cuz you gotta focus on somethin’. You gotta have something you gotta be talking about. You’re gonna say: The living Pat is on Screw, on the tapes, on the birthday tapes. In and through Screw every day can be Pat’s birthday. These are just experiments, anyway. And you come to right kind of invocation on the last Pat’s birthday tape. It’s on that tape that “Don’t Stop the Music” comes around one more time for the last time. It was Screw gave Pat his, this gift you don’t forget, “Tops Drop.” “This for that Mr. Fat Pat album comin’ out in February…. Bounce bounce to this. Bounce bounce to this.” And the not-stopping, tops-dropping music marks for us a message: Happy birthday, Pat. Pat’s brother was H.A.W.K., Big Hawk. He can be heard on DJ Screw’s 5:00 AM tape saying “What’s up? Goin’ down! In here with that Screw….” Calling crazily from the clouds to whoever he sees. He’s a clicking poet, the prophet of the Screwed Up Click. He’s about to break us off something y’all. Feeling the lean before the lean, the freestyle before the freestyle. That’s the trace. There’s the human element, man. Leanin’ out of the sound out of your mind, the man who made this music, the “Man!,” he lets lean out. Lullabying you. Let it go. Let it loop around and lean you forever for it to evoke the guy. He is not as fly as Fat Pat and he is also not as portly. He’s a little bit headier than his brother. He’s older and wiser. He says he hides secrets in his temple, and his temple is that of a lunatic. Remember Holderlin, student of the same Romantic movement as Mozart, a prophet poet who was later pent up in a sanitarium for forty years? In H.A.W.K.’s life had been trials that would have been unfathomable for Holderlin. But somehow, Holderlin and H.A.W.K., they are writing or saying or singing the same things: that there’s nothing outside of your mind. That there’s a crazy guy peeping in your window and can see that your mind is an ordinary mind. And that no-mind is ordinary mind. The transcendent fragment is just a figment, a semblance. Imagine Fat Pat’s not-as-fly brother, Big Hawk, on a freestyle singing his mind with no faintness, fearlessly, which is with no-mind. And his no-mind is an ordinary one, which is a dark and down one. It’s Holderlin’s; it’s a psychic hell that hypnotizes him like us. It’s from down in there where he sings, hypnotically slowly, “You just met the man with the hand that rocks the cradle. / I keep my 4-5 ready for my enemies, / A homicidal maniac with suicidal tendencies.” Then later, more politically, more psychologically: “King had a dream that we shall overcome. / But if he saw my last night’s he would certainly feel dumb.” It’s an urgent poem sung in his head, singing darkness, the ghostliness, the secrecy and the lunacy, the paranoia and the paranoia and the paranoia. It’s all in his head. This is suddenly the downest, darkest, blowedest, throwedest music there is. H.A.W.K. is a crazed murderer. H.A.W.K. is waiting for us, behind us. “I’ll sneak ya from the back and do a 7-8-1,” he says. He is excited about it. And then at the end of the freestyle that excitement buoys him over into giddiness again, the kind of lovable eagerness for the moment. “Man!” he exclaims. He did it; he’s done. You can reach out and grab him again; he’s ceased to lurk in “the shadows of the world,” as Holderlin might say, in this case about his cosmic co-writer, H.A.W.K., his head. The beat has begun to molasses in again to what you hear. H.A.W.K. floats around a moat in his mind on it and then yells, “This beat’s so dope!,” like he sees land. Paradise, where Screw and Pat are still hanging and banging. IV In 2006, not too long before his own decease, H.A.W.K. released one of his most memorable songs, “I’d Rather Bang Screw.” The beat twinkles through the clouds from that paradise place. That paradise place is also the place of Screw’s mixer; in the recesses of the wiring of his set-up ghosts live together amicably with memories’ molasses. With Screw’s molasses. It seeps into this tribute to it, too, as H.A.W.K.’s panegyric to Screw is screwed up. “I’d Rather Bang Screw” borrows the tune of “I’d Rather Be With You,” by Bootsy Collins. The hook croons out, “I’d Rather Bang Screwwoo, yeah. Said, I’d rather bang my Screw.” It’s a fantasy of mourning, like this requiem is supposed to be. “The whole world dripping candy and jamming Screw.” If H.A.W.K.’s brain is a hell, well we’re marooned in it on an island whose waterfalls fall Fanta, misting candied sugar across a liquorice land and onto the parapets of gumdrop castles. And we’re on this island reminiscing about memorable freestyles. It’s all about memorability. Remember the one on "Peeping in my Window"? H.A.W.K.’s there with Lil’ Keke — the guy who would go on to say, “Pat was everything,” remember? — who’s looping forever. The beat is this creepy peeper track, a peering-over-the-apple-pied-windowsill-into-the-family-room kind of track, and even when it runs out, even after the last little nimble piano chord, he raps. He wraps it; and his raps wrap around a short verse by H.A.W.K. in which he, H.A.W.K., and Holderlin, both, say / sing how “Shit’s gettin’ sunny,” before losing its irony to throwed hysterics. How could it be getting sunny? Maybe we’re on a candy island but if we look up it still looks like we’re in hell. That is, in our heads. It’s incredible that these guys just got together, just a bunch of friends right, and became a thing. They started their own labels and released their own records. It’s like a bunch of friends trading demos basically — at demo-trading level, you know — going over to Screw’s house, putting a freestyle down and the next year they’re putting out a record. And they’re dead now, you know. Gone to Paradise. You know that, right? Yeah. Cuz you know, paper-signing takes a long time. Autographs. Marks. Checks and shit. Success, the sound—sunny shit. It took years back then. If it were now…. V Cuz this is technology talking, and the technology was slower back then. Screw had a system that was kitted out for the ghost that lived in there. A finished attic of sound, wires running all through it, where the ghost had a bed, a lamp, and a mirror—he’d hang out in there swirling songs through his throat, sucking the song’s up and puffing them out, and that’s how DJ Screw’s tapes came to get their distinctive sound. He had a system later where he’d write a letter that detailed what he wanted to do to whatever song. Wrote on there, for example, “Slow down through “Dead End Representative.” Chop up “Heart of a Hustler.” And then he’d put the letter in the envelope and stamp on it, and then slip it into the cracks of the mixer. There’s that space between the thing that has the crossfader on it and the box that protects the wires and the attic for the ghost. And he’d slide it in there and it would float down to where another ghost lived, a ghost so far down it could only be summoned by letter, and that ghost would spring up and meet the message and make it, would do Screw’s dreams, however outlandish they might’ve been. VI So I just wanna put in a good word for the man, express my appreciation for what went down. I wanna let me let me figure out how to articulate my message for Screw and his crew in a way that matches his method—to let me do for screw what screw for me did. But you’d be waiting a while, it’d be slow going even to get to where it could be more appropriately slow-going. And in this slow-intro-into is H.A.W.K.’s encomium just an effort at buying some time to figure things out. It’s a Fat Pat freestyle, inflected with ineffability and uh...what can I say? Impossibility, infinity, melancholy, mourning—and not just for Screw, too, but for all these words I so far have written. It seems like kind of a drag to re-mark so mournfully after Screw while my intention is only to show some love for him, not for the afterlife only, to show only unconditional love…. VII I wanna start over before the end here, rewinding for a moment, a minute here, back before the messages, before the Mozart. Cuz what I’m trying to say is, Screw is tape-making still, chopped, free and feeling and floating, screwed, and isn’t it to re-mark, isn’t it to write-mark, isn’t it to write dark if I’m gonna type this thing about his music like I’m trying to use it, isn’t it to cop him, isn’t it to drop him, like he’s really gone, like he’s really thrown, ain’t around town, is it gettin’ you down, to listen to the sound, that’s coming from the ground? So I’m gonna try to say something else, to save something, which is to say that, again, again, chopping it, I’m not even writing about chopped and screwed, screwing it. My fingers on the keys seek to see the calling up from the ground the up of Screw’s screwing it, the screwed-up sound—without screwing it up. It isn’t a biography and it isn’t a review, this right here. I’m trying to write a requiem right here. This is my piece to write. When Mozart wrote his Requiem…. What it is is this is that music of mine, as a marker. It’s the kind of thing to lull you into knowing it right before you sleep. Like a laying back, a slow-listening levitating on Screw, into a loss of yourself. So there’s a moment I always rewind to on the Ridin’ Dirty tape, about 36 minutes in, where Bun B I think or maybe Screw himself says something like “I think that boy want that old school.” Then Screw comes in with the beat like it’s a fuckin’ UFO landing in the middle of the neighborhood really so smooth such that though you know it’s a beat that I wouldn’t even call a beat—it’s a melody—what you hear is your mind starting leaning back in its lawn chair taking a sip of soda finally closin’ its eyes, breathin’ in real deep, laid back, levitating, losing it. Then Bun B is like “Yeah….” And in the next moment Pimp C gets up from rolling joints to freestyle on the microphone. The thing was like his intro music. But what it is is this warmth and relaxation that lingers high over all other Screw songs. It’s your bed to ride on through the dream of Screw’s tape. Rest on it. Requeiscat in pas. VIII Slow I just wanna express that in this here my piece. My appreciation. My unconditional love. For what he did. For what he did. Not for me, but for art. Those haunted sounds that make an art that touches the living, that rests their heads. The dead can gather in a circle round it and look upside-down at their markers, their filers, their archivists. They can look at it and read what it says about that haunted art that is the art that Screw came out with. That came out in his suburban houses, driving slow-low-and-bangin’ hearses with. That’s it, man. That’s it, my piece, my pas. Watch it. Keep your eyes on your motherfuckin’ screw. When you get this screw right here, I want you to hold onto this motherfucker. Cuz we’re gonna come up. We’re trying to let the whole world know. Don’t say that I didn’t warn you. So that’s it.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Blog Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed