|

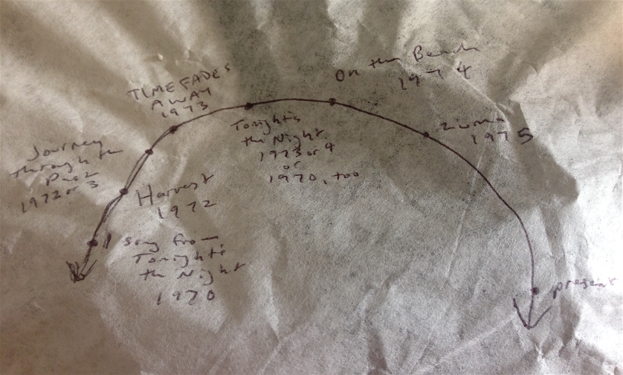

Written by Allan Kiddings Part two of a three part series that relays a story about a writer and his journey with Neil Young's music, with this part covering On the Beach and Tonight's the Night. III It’s like you’re on the beach, but you’re bummed; are you beach bummed? In the title track on On the Beach Neil says things like when he says, “I need a crowd of people, but I can’t face them day-to-day;” or, “Though my problems are meaningless, that don’t make them go away;” and “Now I’m living out here on the beach, but those seagulls are still out of reach.” He says these sorts of things as though there with the sand in his sandals, one hand slopped with ice cream popsicle melt and chocolate smudge, also sandy, also the other maybe just kind of awkwardly pressed against his chest, begging a pardon or else swearing by the melty slop of ten years’ commandments that this is how it is, this summer. A plain-as-the-weather-forecast commentary, from that guy who gave us all those straw-hat songs to listen to while you’re rowing out from the confluence and docking on the beach. This summer, seeming to come for him as for us from a place deeper than time, a place that only he knows of, an isolated reef, asks, “Do you get it, that sometimes summer’s like the way it sounds on this album, On the Beach?” A beach to be sad, to be out there sad in the sand. Way out there. You remember out there at Praia do Futuro, the beach of the future, out there sitting on a wooden stool beneath the palm fronds and the out-of-reach seagulls, sitting there with your feet in the sand in the shadows, on the beach and you were sitting there drinking Brahma beers? Looks delicious; tastes like a Budweiser (it is a Budweiser)? The Brahma king of the beach. Brahma the beach god. “The god Brahma,” it states somewhere in the Bhagava Wikipedia, “emerges at the moment when time and the universe are born.” So that must’ve been what it was you were out there drinking in: the universal time, the moment at which time and the universe are born; it’s all relative; flashed in from the past to the beach of the future. And you were out there with the seagulls, relative to them, blankly taking it all in like them, like a beach bum. Who cares? Who’s watching you? Slum around the beach bummed out if you want. Look straight up into the sun and gurgle. Stand up and brush the sand from your belly hair. Trudge out to the beach’s edge and catch the beach bus to the bus terminal, sandaled. I went to a lot of beaches in Fortaleza, Brazil in the year that I lived there. A lot of beaches. And I listened to a lot of On the Beach. It was my companion, sandy as me and also as sad. Neil says that at the time On the Beach was recorded things were getting, “Pretty dark. Not really that happy. I think it was a period of disillusionment about things turning out differently than I had anticipated.” The things that’ll disillusion you, you know. Yet the thing is, what the hell is he talking about? He would tell Cameron Crowe in 1975 that On the Beach was “‘Probably one of the most depressing records I’ve ever made,’” remembering it like that after Tonight’s the Night was due to come out in a couple of weeks. He had Tonight’s the Night on the brain, because from what I can tell Neil told Cameron Crowe that most-depressing-thinking thing, thinking of those disillusioning things, to tuck the facts of that time recording On the Beach back behind Tonight’s the Night’s black. Because it sounds to me like they had a hell of a time recording this album, On the Beach. Not as bleak as Tonight’s the Night, which they — Neil, Crazy Horse and company — had recorded before, back in 1973 or whenever it was. They recorded Tonight’s the Night and shelved it, and then took on On the Beach like it could sound the warning signal before that sunken boat of a record, Tonight’s the Night, went down. Here’s what I heard, or read as it were, from Neil’s biographer: The [On the Beach] sessions took place at Sunset Sound and the players began to congregate at the Sunset Marquis Hotel. It was a nonstop sleazefest, with odd visitors popping in and out. One night it might the Everly Brothers, the next a Playboy bunny or two…. “We were all crazier than shithouse rats,” said [bassist Tim] Drummond fondly. “Hollywood Babylon at its fullest.” Full of sordid facts littered in the tape’s tale like tequila bottles, B12-shot canisters, sludgy honey-coated marijuana treats smoldering on the floor. “People passed out.” “Rusty would pour [the stuff] down your throat and within ten minutes you were catatonic.” Neil would remark that it was “Pretty innaresting stuff.” “Rusty was there at the hotel cookin’ honey slides, burnin’ holes in the rug.” And so, “Room one at the Sunset Marquis soon registered the effects of [Rusty] Kershaw’s debauchery.” Or so it reads or is heard from yet another excerpt from the bio: “Red-wine stains covered the carpet, which was also dotted by cigarette burns commemorating the Cajun’s drug-induced nods. Visitors were awestruck by the extent of the wreckage. ‘It was like cannibals had been livin’ in there,’ said Drummond….” There was also a Hooker’s Ball, a monkey with “great big soft furry lips,” a case of bags of Fritos, a white convertible Confidential Lincoln Continental, a talismanic palm tree, and a pool; and nailed to the Hollywood Babylon hotel room door with a pocket-knife was a note that advised, “DON’T.” “Not ‘Don’t do this, don’t do that’ — just DON’T.” Most of these artifacts of wildness were attributed to Rusty Kershaw, an overall-clad guitarist from the swamp. He had a powerful influence on On the Beach. He’d cozy up next to Neil in the studio and would explain to him, “‘Neil, you carry a heavy vibe, and if I’m sittin’ close to you, I can feel what you feel before you play. I know where you’re gonna go.’” Sounds like the devil on Neil’s shoulder — is how the album sounds, too, like a seedy and slow-going Bo Diddley’s Beach Party, in hell. Sounds like the ancient bayou god of the underworld was composing a jug symphony, with a genius singing. “It was,” according to Neil himself, “very mellow, very down — not depressing. Honey slides. Good album.” One of my favorites, in fact. What else can you say? That’s what I would’ve said while in Brazil, anyway, when I was on the beach with On the Beach. I’d be a hundred-yards-walked along a dingy boardwalk beside the beach, even, with a statue of a siren seamstress who inspired a gang of naval troops before battle, ogling the toothless fishermen who you can read about in Frommer’s, with some white Apple-brand earbuds’ cord dangling from my ears, warily listening to On the Beach, “deep inside myself, but I’ll get out somehow.” Of course, I wanted to get out; I wanted if I could to walk all the way out there. Past the beach. Bend myself to be a different guy. Leave the old me behind, a beached body, with the Brahma. Of course I wanted to put myself out there and become Brazilian by degrees, by the tropical heat, by the nights out, by tequila bottles or cachaça shots in plastic cups. By jaunts downtown, haunting all the beach shacks on the boardwalk seeking conversation, companionship, some quick thrill. Looking for the Babylon of On the Beach on the beach like I was one of those old fogies with a metal detector hobbling listening for precious metals, nightly I’d wander with my earbuds in through bars whose gold and treasures were showered on others only. In other words, I wandered into one place at 4 AM where a lot of young adults sat drunkenly slurping soup. Then another place under an overpass: a simple hot dog stand with ten or twelve plastic patio tables set out and it was crawling with kids. There was another place, I’m starting to remember, at the end of a tin-can-constructed pier just ahead that stayed open over the ocean through the blueblack night, filled to its brim with early-bird boat folk and bedraggled young brats. It stunk like brine. Still, that was where I wanted to get out to; all the way out there so that it would be a drag for me to turn back, the brine smell making it sickening to turn back. But then again, as Neil admonishes us, “I don't want to get down to the point where I can't even get up. I mean there's something to going down there and looking around, but I don't know about sticking around.” And what’s more, once you’re out there, “Sooner or later, it all gets real.” So I’d walk on. I walked on all over the fuckin’ city, next to Neil, afraid for both of us. The beach I remember isn’t supposed to be all that real. “Too honest,” Neil might say. The beach of his was Malibu, and he moved there about six months after On the Beach was released. The album transported him, you might say. First the music, then the waves; the dark ocean roar coming up over the earbuds. The point is, I remember my beach being in Brazil, in Fortaleza, a big city whose name means “fort.” I was living and working there, teaching English three days a week. I’d been the benefactor of a family friend’s family’s hospitality. My living quarters were exceedingly comfortable, and my living expenses were very low. So I had the means, but I hadn’t yet to get the ends. Those frayed ends of life I wanted to walk or wade out to. Instead I’d stay too long in those living quarters I mentioned, counting the unspent money. Sometimes I’d drift out to the balcony. I’d write to the friends I thought I ought to have been hanging out with. “One thing that's kind of a drag is that I don't have anybody to go out with tonight,” I’d complain, “and it's something that of course I'm out here on the balcony, looking out at the city thinking about. I miss having a group of friends. I mean in a way, it's something I've always missed.” Ay coitado, as they say. You poor dear. Other times I’d write to mentors. “Dear Ty” — my old Creative Writing teacher, remember? — I’d write: “I wrote some album reviews that were intended to be sort of prose poems, and like each review was written as though the album was like my summer album — an album that I listened to on the beach in July, for example, and each piece was written in the time of the length of the album. For example, the first one I did was Neil Young's On the Beach, which is like 40 minutes long, so I only gave myself 40 minutes to write the review, and it took as its prompt I guess being on the beach, listening to this album. It was done on a tumblr, here's the link: http://onthebeachinjuly.tumblr.com/. Most of the stuff is pretty lousy, and I use a lot of the same words and concepts a lot, but at least it was practice, and it was fun.” Here’s Neil again, for what it’s worth: “I think if everybody looks back at their own lives they'll realize that they went through something like that. There's periods of depression, periods of elation, optimism and skepticism, the whole thing is.... it just keeps coming in waves.” Here’s the whole damn thing, in fact; cuz what he says in his Hollywood is what I could’ve written from my Fortaleza too: You go down to the beach and watch the same thing, just imagine every wave is a different set of emotions coming in. Just keep coming. As long as you don't ignore it, it'll still be there. If you start shutting yourself off and not letting yourself live through the things that are coming through you, I think that's when people start getting old really fast, that's when they really age. 'Cause they decide that, they're happy to be what they were at a certain time in their lives when they were the happiest, and they say 'that's where I'm gonna be for the rest of my life'. From that minute on they're dead, y'know, just walking around. I try to avoid that. Cuz that’s what I wanted was for it all to be connected, or else I might lose the chance for connecting it. On the bus to the beach, trying to make some sense of it! It being the past and the future. I wanted there to be all connectedness between the hopes and expectations I’d harbored in the past and the fortuitousness of the future, between my trucking to the same L.A. as Neil had been, where I got my travel documents and Neil got his Babylon, and my future beach, the beach of the future, listening to On the Beach. I wanted the fruit of it all to be sticky and connected, with the pulpy juice of the present there in the middle where I was. On the Beach on the bus — a sticky connector bus — from the beach, to the balcony, on the balcony, with On the Beach still. That’s the story, the whole story; there is no other story than that. Me drinking and thinking and writing or typing away out there to folks that were really fuckin’ far away. One night I was out there up there on the balcony having dessert, a decadent custard sort of thing, and doing some writing like I am now except soberer — indeed very sober; I was not ignoring the waves of my condition, in the writing I was doing, I was writing the old story about how dusty the frontiers of human friendship had become, about how isolated is the modern man from his mythological roots — having a mythological name myself (Allan, ha!) and so naturally entertaining an interest in such a matter — about how I didn’t know how to write anymore, or what I wanted to write, because I hadn’t said really anything to or really gone out and done anything with anybody in such a long time and so how could I know? No story. Then I’d write: how about line-dancing in an auction hall with livestock looking on. How about about the graveyard across the street from one of the bus stops downtown, about how old it was and it even had a poured-cement clock in the middle of it tallying the years. About the docks whose shores forbid you to swim in them because of their trash. The foul shores of funk, like a myth. I wrote all about it. Come to think about it, as I’m writing about it now, not much has changed really, save for the sobriety stuff. I’m still out on the beach. It’s just like the beach is a desert island. The point is, if I can reiterate here, I remember. I remember doing some writing on a website I named after Neil’s beach record; the name was On the Beach in July, it being July in Fortaleza. And I remember not having anybody to go out with tonight, tonight not being the night, not yet, and yet nevertheless going out. I’d mope in laps around a bar called the Orbit, looking out for some semblance of un-loneliness. Trying to lose that bad fog. The trick, I see clearly now, would have been to get off the beach without leaving from the beach, and launch into outer space. I’d drink a lot to try for such a trick, landing only nearby at the pool table. When the conceits subsided and the late hour bid me turn back I’d return to the living quarters. And lo, like finally a metal-detector find: an e-mail response awaiting me. Some words about my writing, about the beach, about the No-story: “I love On the Beach in July. First because I'm a big Neil Young fan but had never listened to On the Beach, which seems so odd to me because it's such a great album. Second because the writing is good. Funny and sad. Actually, I think I learned a lot from those album posts…the honesty of speed and removing self-editing. It makes me wonder why even bother with the literary.” That was it — yet a plenty, redemptive it. So then I’d go to sleep, with some finality, with the pleasant sounds of birthday balloons popping filtering in from out there, audible over the fan and the Neil Young fans (two of us), and over also, finally, the time-honoring album whose tide had flooded my Fortaleza. IV Tonight’s the Night begins with a little flicker of some piano keys. Soon after those there creeps in this footsteps-in-the-dark sort of high-hat, and soon after that there’s the bass emerging out of like a profaned ground. These sounds set the scene for a graveyard of an album. And the first ghoul to get up out of there off the beach is Bruce Berry arisen from out of the crypt — like the past was the beach but has since become more macabre, or at least is cryptic. “Bruce Berry was a working man, / he used to load that Econoline van.” He was just a working man. This is the kind of interpretation that lays itself out by describing: his life was in his hand. Late at night he’d pick up a guitar. And he’d sing to himself a song he made up about the tour he was on. And that song’d go “Tonight’s the night. / Tonight’s the night.” Tonight’s the Night almost didn’t come out. “Blame it on that blurry evening at the Chateau Marmont, where Young had played Homegrown back to back with Tonight’s the Night for a bunch of stoned musicians including Rick Danko. ‘At which point Rick the Prick said, ‘Go with the raw one,’” reports the biographer. That’s one of the reel tales — it really happened; get it? It was also really like this, as Neil recollects it (again, the biographer reporting): “It was late at night. We were all pretty fucked up, listenin’ to tapes, on the edge,” Neil remembered. Present were Richard Manuel and Rick Danko of the Band, the great Louisiana singer/songwriter Bobby Charles, Ralph Molina and Billy Talbot of Crazy Horse, maybe others — no one present for this hazy event is quite sure of anything. “Danko, Neil and me were sittin’ around the piano singing,” recalled Molina. “I think we’d done a little meth, because when you do methedrine, the fuckin’ harmonies are so beautiful. We fuckin’ sang and sang. It was Godlike.’ After they listened to Homegrown, Tonight’s the Night — which happened to be on the same reel — came on. “Danko freaked. He said, ‘If you guys don’t release this fuckin’ album, you’re crazy.’” Neil starts “Speakin’ Out” with another anecdote: “I went to the movies the other night. The plot was groovy; it was outta-sight. I sat with my popcorn, not looking for good times. Lost in the cartoon, I grabbed the lifeline.” He’s practically harping on it. Good times are lifelines. Nights are outta-sight. It rhymes! Tonight I’m in a good time, living on the line, traveling from town to town with some old friends of mine, musicians. We’re on tour. I load the van. Like I want to be a musician. Let’s see how it plays out (there’s that piano-flickering again): So I was sitting in a movie of a kind myself when I was listening to that song, on this tour. I’d be down in the audience, about eighteen inches below the stage, looking a little up, you know, with my head at an angle like a crane, like a night-crane in the dark of the place, looking up into what but the lights of the movie. The heat and the light blazing beams down on my looking up. The way it’s stuck in my brain, though, is as though it were in black and white. White light coming down. The band members blotted out in ben-day dots like an old newspaper photo. And the background all night-fall black. And that night was Tonight’s the Night. And the movie was “Speakin’ Out.” I thought, “You’ve finally figured out how to say all the things you’re thinking. Direct your thoughts toward expression. Speak it out. It will out. It will stay fixed in the air between your sober self and your other one forever. Leave it. Let it. Lit et: the bed and of the bed and breakfast last night. Litte: the little of looking a little up, you know.” ‘Let’ — an important drug. We’re takin’ it in on our way to the next town. Then letting and getting up on the stage and speaking out over the mic, “Welcome to Miami Beach; everything is cheaper than it looks.” Everything is in its time. Time was in our hands. Our hands were under and around bulky amplifiers shoving them into the trunk of a minivan and then our hands’d hold the steering wheel for four or five hours. When places had just passed through our view then before long we’d be in some other downtown asking ourselves where are the memories, where did we eat last? Where have we been guaranteed a shower? Where were we when we got high on the beach? How had I lived before this living on the road? Those are some examples. For the first time in as long as I could remember it was the easiest thing to forget everything and pay attention to what was going on. It was the raw, and it was the now. So I paid attention. Now this is making it out to sound a lot more high-falutin’ and expensive than it is. The sound was just one of those ones that set the scene. Nothing more expensive than the macabre dreamland sound of the crypt. That’s the thing, too, about any wild time, is that it always seems to be more gilded, more luxurious, ritzier than it was. Your recollection smooths everything in velvet. Mellows it into a nice satisfying memory. Mellows your mind like “Mellow my mind” casualizes it. Causes it not to quit; it won’t go away. There’s this moment right now toward the end, about a minute from the end, when Neil’s voice cracks amid a dampening crash of the cymbals and all spaced out between spaces and echoes. It’s like the song is a castle with crenelated walls wherein there’s space big enough for cracking voices to take their aim. Afterwards he disappears into trying to recover, playing the fool, buying time. “Ain’t got nothin’ on those feelings / that I ha-a-a-uh-ad.” Until maybe thirty seconds later when he kicks into another final winding verse. I picture Neil here in the absolute shadowed bleakness of SIR Studios where the thing was recorded (where everyone was always wearing sunglasses, a mausoleum for the old gang to be chanted to, a cave for musician-creatures to crawl around in), swaying like he’s getting sucked into a vacuum. The vacuum of the time, right? Cuz you know he recorded Tonight’s the Night before On the Beach, but released it after, right? Here’s a drawing I drew to draw attention to this time vacuum I’m talking about: See? But you couldn’t see in the studio. “‘It was completely black inside, didn’t matter what time it was,” said [photographer] Joel Bernstein…‘I had to get ‘em in daylight. It was like doing a documentary on nocturnal animals pulled out from under a rock.’” A cave, man. A crypt. Boo! And by the way this is all from the bio. Once it was recorded it sat on a shelf like a brain in a jar until the aforementioned fateful night that follows from “It almost didn’t come out.” Then it came out. Just as I was about / to roll another number / for the road. I’ve been listening to Tonight’s the Night an awful lot on the road. My impression is, there is no more exact way to explain Tonight’s the Night than the way others have already explained it: “That’s the one about everybody dead? I can’t stand it. No way. I’ve never played it all the way through and I ain’t gonna play it…. Ruins me. No thanks.” That’s what Neil’s mom said about it. Others say, “I couldn’t believe all that weird slide...all those shades of melancholy that were in us...it’s almost Middle-Eastern, like ‘Ben Keith Goes to East Cairo.’” That’s Nils Lofgren. “Surrounded by friends, his subconscious unhinged, he had tuned in to the cosmos.” That’s the ol’ biographer, Jimmy McDonough. “A drunken Irish wake,” which is how Billy Talbot described the sessions, which is how I’m plagiarizing it here from Jimmy McDonough page 412, which is how Pitchfork plagiarized it. And, after all, “essential,” is what Neil’s dad said; it’s an album of “a man on a binge at a wake, a long happy bout of not giving a shit.” Page 434. I also read a lot of McDonough on the road. Meanwhile Neil was on tour himself — the Tonight’s the Night revue. Complete with glitter shoes, a wooden Indian who played guitar, jeers from the audience, joints from the audience, gallons of tequila, t-shirts with charming slogans like EVERYTHING’S CHEAPER THAN IT LOOKS and EQUAL TIME FOR PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE, and Neil the whole time looking like Charles Manson. According to the Bible I’ve been quoting, “He rambled on about Miami, made obscure references...then played new song after new song. ‘Here’s one you’ve heard before,’ he would mutter toward the end of the night, and the relieved audience would start to applaud. Then he’d lurch into ‘Tonight’s the Night’ for the third time.” What a riot, I thought. And indeed a riot is exactly what it was at a show in jolly old England. No one got it, I guess. Neil told them, as he backed off stage into the wings, “Elvis has left the arena, ladies and gentlemen.” I love this story. You have to lookout if you’re gonna go all the way. Folks’ll be comin’ for you, for your good times. “I was havin’ a fantastic time,” Neil says of this time. “It was dark but it was good. That was a band with a reason.” Did I have a reason? Those times were good times. They were times I had the company of friends everywhere I went. It was a good time for me to forget what came before it. A good enough time. Because it’s good enough to forget at certain times, on certain specific nights, be they close in proximity to the present or not, since it’ll open out to remembering for you your friends. And I made a lot of friends in the process, is what I’ll say of this time. I had gotten far enough out there. I was ready to lay aside the shitty time from the past in order for the good times to happen, and then to pass — to happen to pass through us. Tonight’s the Night was for Neil as for me an emergence of badass-ness that was always like inherent; a kinesthetic build-up of fuck-it-all, exploding here, tonight, for cheap. Tonight’s the Night was a cape for me to wear as I walked my walk into that ol’ familiar boxing ring we’ve all got in our heads of having to tell yourself that you’re a good guy. It became a vibrant place for me despite the dampness or maybe because of the dampness of this crenelated crusty-ass album. I liked being in that ring because I was always assured by the badass croons of Tonight I’d win. It was a relief to be off the beach. It doesn’t matter where you are if you don’t have people to hang out with. It doesn’t. But then what is it? It does what? What does it? (There’s that piano-flickering again.) I was in a place where I could give myself some advice. I’d tell myself, “Please take my advice: ‘If you're gonna put a record on at 11:00 in the morning, don't put on Tonight's the Night.’” Advice after Neil. And as wise ol’ familiar friendly Neil also said, “You have to get in to be here.” That place; it was this place, now. And to be in there was to see — see here, friend. Let me share this with you. I’m just now a gregarious guy. So it’s not a big deal for me to share this stuff with you. Please take my advice, and do it; look: Tonight’s the Night. “Tonight’s the Night.” “Lookout Joe.” Looking out for myself here. Look: The liner notes. See the beach? What’s it to you now? On tour my old friends asked me one night, “Do you get it? There isn’t a difference between the first “Tonight’s the Night” and the last; they’re just the same song two times. They are first and last both. Same. Not even in their first-and-last-ness, not even in the time between them, do they differ. They pound their separate breaths against the microphone as one. If I ever were to think about it theoretically, as I hoped I’d never do but I will, I’d say they were “not one, not two.” They float beyond the concept of time — cuz they both instantiate tonight as the Night, in each moment as the present passes through you, not one, not two. “Tonight’s the Night” and I guess I like the first one better to take me back to the beginning, where those piano keys are still flickering. Read part three here.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Blog Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed