|

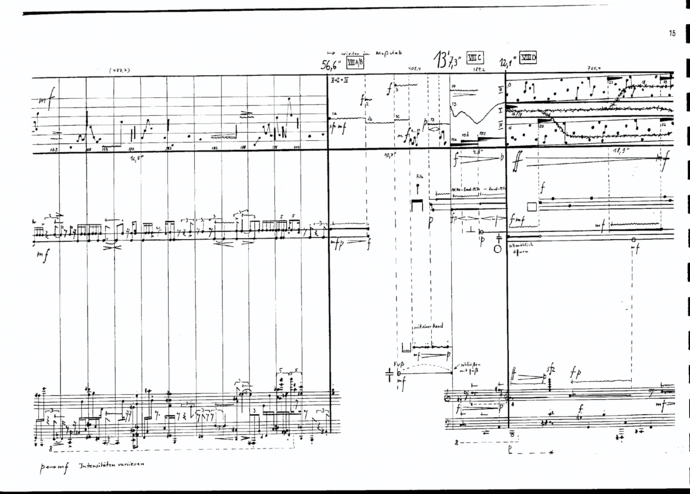

Written by Kaylee Orem Kontakte, a 1960's composition from musique concrete composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, utilizes innovative and complex techniques to manipulate perception of time. This piece discusses the techniques Stockhausen explores to draw the listeners toward experiencing time in the present, as well as the inspiration with a focus on the ability to analyze sound in relation to time. What is sound? Think about all the different possible sounds heard throughout the day. Cars passing by, the chattering of people talking, keys jingling in your pocket, music playing in the grocery store, the microwave humming, the list goes on and on. Whether we are aware of them or not, we are constantly hearing sounds happening all around us. Now, let’s change gears for just a moment as I pose another question. What is time? Time is an interesting concept, used to measure the moments of our lives as we are moving through them. Time can be thought of numerically, graphing out the hours of the day to an individual’s specific schedule; however, oftentimes we find ourselves perceiving time in the future, (when we need to get things done, when we have to get to a certain place), and in the past (through nostalgia, regret, and desire for second chances), but how often is the full attention of the mind concentrated on the moment happening in the present? What if somehow sound could be used as a tool to experience time in this way? Composer Karlheinz Stockhausen takes this idea of perceiving time as it occurs in his piece Kontakte, where he experiments with untraditional uses of sounds, form, and spatial positioning. Karlheinz Stockhausen was born in Cologne, Germany in 1928.He first began studying musique concrete in 1951, a technique that takes recorded sounds on tape and modifies them through various ways, i.e. shortening, cutting and splicing together, playing backwards. It was not long after this that Kontakte was composed, during the years of 1959-1960.The name derived from Stockhausen’s concept of creating a series of forms of contacts between the two sound groups, instrumental and electronic, whereas the electronic works as a mediator between the different families of instruments as well as to extend the behavior of sound beyond what conventional instruments practice.The 34.5 minute piece is composed for four-track tape, which can either be listened to alone or as another version accompanied with piano and percussion. The combined version, which contains the piano and percussion, is intended for concert performances with four speakers distributing the electronic sounds; whereas the electronic version’s purpose is designed for at-home listening.When performed as the combined version there is one pianist and one percussionist, and the pianist will also play some percussion instruments. The piece had originally called for four performers, and points of improvisation, but during trials of performing it became clear that this arrangement would have to be altered due to the difficulties of synchronization with the tape. As a result, Stockhausen ended up explicitly defining the composition, and also dropped the performer count from four to two. This extreme detail includes a freer system of serialism, a compositional technique in which elements of the music are written based on a fixed set of rules. In this piece what is being serialized are the “transformative value” including the parameters of space, form, tempo, register, dynamics, and instruments. Stockhausen used a system to alter these parameters that described the amount of change on a scale from 1 to 6, where 1 is smallest possible change and 6 is the greatest possible change.For example, if the tempo was moving at a quick pace and then had a 5 applied to it, the performer has the option to change the tempo fairly drastically, resulting with a much slower pace. Stockhausen was even very particular about the specific positioning of the instrumentalist on stage, using the parameter of space with the purpose of articulating his vision of hearing at one point in time. Stockhausen was able to use the space in several different ways to bring specific sounds to the listener’s attention. The tape alone has spatial qualities that aid the listener in picking apart the texture and place focus on specific timbres sounding in the moment. This is accomplished through the use of different channels. Stockhausen designated four channels to be used with the electronic portion, and each channel is assigned a specific placement in the speakers, from left, right, front, and behind. When listening to the piece it is very evident that the sounds are coming from different sources, and this movement of sound within the space brings their timbre and “rhythmic” qualities to attention as they come and go, almost as if living organisms portraying individual characters capable of waltzing in and out of the listeners ear. In the universal edition of the score for electronic tape, piano and percussion, it's revealed that these movements through space are not at random. The score represents the placement of the sound in the speakers with roman numerals, I - left, II - front, III- right, IV - behind. The roman numerals help as a visual to see where the sound is going to emerge from. They can be combined either with a slash between them, or as numerators and denominators. In the latter the sound would be separated by layer, so if there was a roman numeral combination of II over IV it would indicate that one layer of sound will be directed out the front speaker, while the other comes out the back. If listening intently one may notice that the distribution of sound through the speakers often follow a pattern, and specific techniques can be heard being utilized many times. Stockhausen designated four different techniques that he labels within the score. The first, alternierend, has the sound continuously alternating between the indicated loudspeakers. Rotation, the next technique, does just that, rotating sounds at a designated speed between the right and left speakers, while some sound remains fixed within 1 or 2 of the speakers. Another technique Stockhausen displays is a layering effect where the sound is heard through one speaker, but then immediately in another causing a sense of flooding, which he called flutklang. The final technique he denotes in the score is called schleifen and it imitates a spiral feeling, sending the sound rotating through a looping pattern through the four speakers. Through the use of these four techniques Stockhausen is quite effective in accentuating the sound being heard in that moment. The listener can’t help but become aware of its presence as the sound travels through her ear, dancing from one direction to another, leading her mind to perceive the sound in an encompassing manner. These expressions of sound through space are able to be experienced best in headphones, or in the placement of the four loud speakers in a live performance. Stockhausen uses the set of the stage to bring more spatial interest to the piece. He executes this by placing the piano as far on the left side, and the percussionist as far to the right as possible, and then puts the late tam tam in the middle. The audience experiences the sound of the piano coming from a different placement in their minds than the percussionist (besides the few percussion instruments played by piano). All of theses factors contribute to the use of space to allow the listeners to focus on the specific sounds occurring in a single moment in time. Not only is space relaying this goal of hearing in the “now”, but the types of sounds themselves have unique qualities that demand the listeners focus. The sounds on the tape alone are quite unusual, and even frightening at times, with timbres ranging from soft, atmospheric, and breath-like, to harsh, sporadic, and metallic. Stockhausen achieved these diverse sounds by experimenting with an impulse generator and with interesting ways of recording and editing the pulses created. There is one quote of Stockhausen describing one such technique, telling of “…loops running everywhere, and you could see it through the glass windows between the studios….I used the fast-forward on the tape recorder to accelerate the tapes….the result went up another four octaves, so then I was up eight octaves.” By playing the recording on a loop and then rerecording it as it ran for hours, Stockhausen was able to create thick textures and interesting manipulated sounds. He also was able to alter the pitch of sounds as he mentioned fast forwarding the tapes, so altering the speed to reach the desired frequencies he wanted to achieve. Creating these sounds for tape was a very complicated and tedious process, but it wasn’t the only way he achieved such unique sounds. In the combined version of the piece, Stockhausen introduces a whole new array of timbres with the piano and percussion. The piano was an ideal choice because of its wide range of pitches, and ability to sound multiple notes at once. It can also have timbral changes of its own through use of pedal and attack of the keys. Percussion also seems like a logical choice as it provides for vast amount of timbres. The percussionist’s instruments used in this piece are two African drums (each with 2 pitches, F3, Bb3, E4, and A4), a marimbaphone sounding from E3-C7, 3 tom-toms which were altered to have plywood glued on in place of the membrane to create a dryer sound, a guero fixed to a stand, one hanging rattle of bamboo claves, two wood blocks, four cowbells, thirteen symbols, one small tamtam, one cymbol, one hihat, a bundle of small indian bells, one bongo and three to four tom-toms without alterations, a bongo turned upside down with beans inside to roll around when shaken, one slide drum with snares, and one large tamtam and gong. Just from reading this list one can see the diverse timbres chosen, and the specific alterations that Stockhausen carefully thought out to create a rare and unusual sounds. When he chose which instruments he had in mind six categories based on timbre. He broke the timbres into three categories, membrane, wood, and metal, and then he made broadened these into two more categories of noise and sound, or musical tones. So each timbre could either be classified as noise or as having a musical tone—in other words sound. Stockhausen’s intention was that these instruments could be used in a way that caused for an even chain to timbres transitioning from dull to bright. This collection of timbres also allows for the “contact” between the instruments and tape to connect in interesting and texturally diverse ways, which can be rhythmically interlocking or even used to create untraditional harmonic relationships. By taking such thought in crafting the timbral experience the listener would have, Stockhausen created a more focused realization of the sounds occurring in the ongoing timeline of the piece. Now that I've discussed both the use of space and sound to bring attention to each passing moment, let us take a look at form and time. “A given moment is not merely regarded as the consequence of the previous one and the prelude to the coming one, but as something individual, independent, and centered in itself, capable of existing on its own.” This quote of Stockhausen describes the mentality behind what he likes to call “moment form.” This concept plays with the idea that the focus of a person’s attention shouldn’t be on the relationship of how the current moment relates to the past of further moments, but instead how it simply exists during that point in time. Kontakte does not lead the listener in any direction or formal structure, but instead takes the listener on a journey through the exploration of sound relationships. Think of the traditional sonata form: material is presented and established, then it is developed and takes on a new personality, and then it finds its way back to the original material leading to a clear-cut finish on a strong perfect and authentic cadence. This is not the case for Kontakte. Not only is the piece absent of motivic material, but it also contains no driving motion. There is no forward moving idea and no goal to be reached; it never actually finishes, but instead simply comes to an end. It is important to take into consideration that the form of this piece could be constructed through the structures, sixteen of them, that make up the piece. Earlier there was mention of the use of a free form of serialism attached to the parameters of transformative qualities in the music such as dynamics, space, register, etc. This is the way Stockhausen went about contracting the overall plan of the composition, by applying these transformative alternatives of change within each parameter. For example by a dynamic level notated at p could have a 6 assigned to it, meaning it will have the greatest possible change and move to f or even ff. These transformative alternatives to the parameters are taken and added together, and with that sum partial structures are created. Although there is great detail and planning involved in the creation of the structures of the piece, they do not necessarily relate from one structure to the next, but instead have a purpose of creating an ordered sound to be perceived in the moment it occurs against the sporadic nature of the overall piece. Therefore, each structure can be thought of as a specific moment of the transformative parameters that the listener focuses on. Within these structures are even more specific substructures, where Stockhausen explores with the different timbres, instruments, registers, forms, tempos, and dynamics to be experienced in their fullness at that the exact point of incidence. In these ways, Kontakte takes the listener to a new level of perception. By removing the traditional sense of directional form, melodic focus, and harmonic stability the interrelations between the timbres of percussion, piano, and electronic tape moving in time become the object of focus. The engagement of the listener becomes centered around the focus on each passing sound in the moment, accomplished through the use of space and layering of interesting timbres. With no sense of direction, the piece can be experienced at any given point in time, having no real beginning or end. In Stockhausen’s words “They are a form in a state of always having already commenced, which could go on as they are for an eternity….an eternity which does not begin at the end of time, but which is present in every moment.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Blog Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed