|

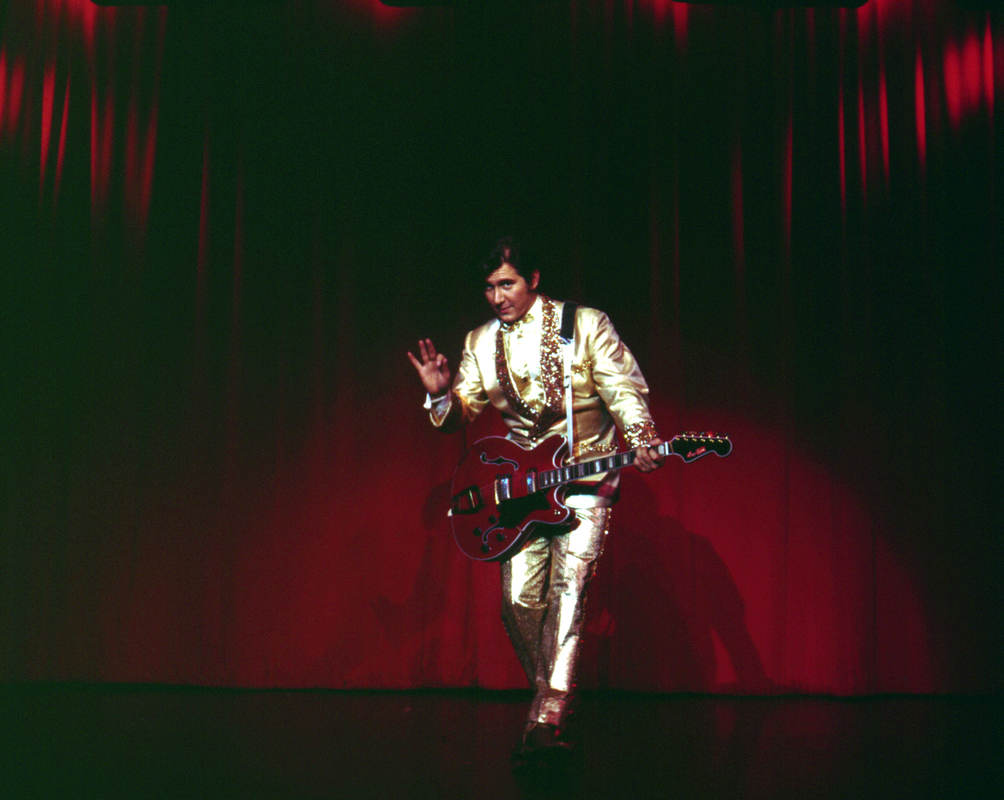

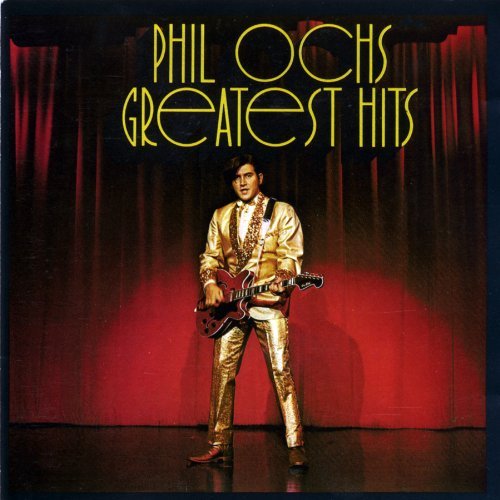

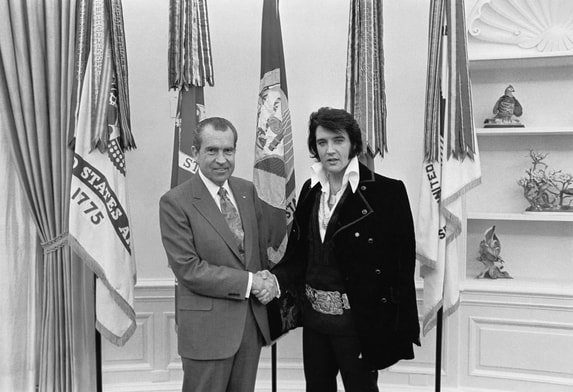

Written by Alan Kiddings A lot of things changed between 1968 and 1970. We landed on the moon. Lots of protests and assassinations. Elvis came back. And a beloved folksinger, not quite as well known as Elvis, but with grand aspirations, and a gold suit, reinvented himself. I On March 27, 1970, the folksinger Phil Ochs, wearing a gold lamé Nudie suit, performed two sets at Carnegie Hall in New York City. Both sets included medleys of songs Elvis Presley made famous—”Ready Teddy,” “All Shook Up,” “Heartbreak Hotel,” and others. These songs were not in the folk music canon; the audience at Carnegie Hall had expected to hear inspiring Ochs originals like “There but for Fortune,” “Outside of a Small Circle of Friends,” “I Ain’t Marching Anymore” Many booed Ochs’s medleys. Ochs responded, “Let’s not be narrow-minded Americans. You can be a bigot from all sides. You can be a bigot against Blacks, you can be a bigot against music, you know? I think what we’re doing up here is music; I think it should be heard.” It would be five years before A&M Records agreed to release an album of this concert material: Gunfight at Carnegie Hall. II A month prior to the Carnegie Hall concert, in February 1970, Elvis was performing nightly at the International Hotel in Las Vegas. His show would prove that the King had really returned. What began in 1968 as a desperate idea for a Christmas special had unfolded into a full-on comeback. Elvis had performed at the International in 1969 with great success. By 1970, Elvis had signed a lucrative deal with International Hotel owner Kirk Kerkorian: he would perform every February and August, and would receive a million-dollar annual salary, for the next five years. As Elvis told music critic Frank Lieberman, “I was human again. There was hope for the future.” Like Ochs, Elvis would surprise his audience with his choice of material for these Vegas shows. The setlist was comprised mostly of songs either recently or never-before recorded by Elvis. He would cover Neil Diamond and Mac Davis to demonstrate his taste for contemporary pop. He would dip into some hippie-inflected southern rock songs that had recently become hits for Creedence Clearwater Revival and Joe South. From his own catalog he would play only “Suspicious Minds,” the obligatory “Can’t Help Falling in Love,” and a few others. Unlike Ochs’s audience, Elvis’s would love it. The opening night of these shows was crowded with celebrities. Among Dean Martin, Fats Domino, and other musicians in attendance was Phil Ochs. III In the same month, Ochs released his Greatest Hits album, which consisted entirely of new material. The album, produced by fellow folk figure and Ochs’s L.A. neighbor Van Dyke Parks, opens with a song called “One Way Ticket Home.” The song features the lines: Elvis Presley is the king I was at his crowning. My life just passed before my eyes I must be drowning. It was recorded on one of the two days Ochs and Parks spent in the studio for Greatest Hits. After seeing Elvis at the International, Ochs wanted to reinvent himself as the Elvis of the Left, the Lefty folksinger with real pop appeal, “the combination of Elvis Presley and Che Guevara.” The prospect excited him. He had always been an Elvis fan, from the time he was first interested in music. In college Ochs had even decorated his dorm room with film stills of Elvis in Love Me Tender and Loving You. Now Elvis was his role; Ochs would act him out, apply him to the radical politics of the time. The old Elvis. The Elvis that had come back. Despite the drasticness of this change of image for Ochs, and the unlikelihood of its commercial success, it was not a joke. IV Before his tenure at the International, Elvis had not played a show in Vegas since 1956, when he and his original band from Memphis served up sub-par performances for a “strictly adult audience.” Among the adults at one of those shows was Liberace, whose autograph Elvis procured for his mother. When Elvis went back to Las Vegas later in 1956, as a kind of getaway from the premiere of Love Me Tender, he saw Liberace’s show at the Riviera. Liberace, wearing a gold-sequined jacket and matching pants, pointed out Elvis in the front row. After the show the two entertainers exchanged jackets. Four months later, at a show in Chicago in 1957, Elvis debuted the all-gold Nudie suit he would wear on the cover of his second gold-records compilation, 50,000,000 Elvis Fans Can’t Be Wrong. A decade later, Ochs parodied himself or Elvis or the suit or all three on the back of his Greatest Hits album. Ochs had been involved in Leftist politics for much of his adult life. He began his performing career at a peace rally in Ohio, and had consistently played a part in other peace, civil and human rights, and anti-Vietnam demonstrations throughout the 1960s. The FBI started surveilling Ochs in 1963, when he published an article of appreciation for Woody Guthrie. The FBI maintained an active file on Ochs until after his death, chronicling many of his publications and appearances, and citing some of his song lyrics. In 1967, as noted in the FBI file and elsewhere, Ochs had helped to organize the “War Is Over” rallies in Los Angeles and New York City. In 1968, Ochs aligned himself with the Yippies, the Youth International Party founded by Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin. With them, and with many other musicians, artists, writers, and young political figures, he went to Chicago in August 1968 to protest the Democratic National Convention. Like them, he was arrested: they had brought a pig into the convention hall to nominate him for president, but they had neglected to pick up a permit for bringing livestock into Chicago. Ochs and the Yippies were released on bail. Back on the street, they were confronted with the violent and chaotic scene that had gripped the city. They persisted in trying to minimize the violence and promote the Yippies’ platform, but mostly without consequence. The riot significantly altered--darkened, dampened--Ochs’s thinking. Ochs retreated to Mexico for a while. Soon after he returned, the FBI called Ochs to talk about Chicago. This call seems to have galvanized Ochs. He wanted to make another album. As one of his biographers describes it, “The album was a two-act musical, dramatizing the transformation of democracy to dictatorship, and of Phil Ochs, troubadour, into the King of Cowboys. Chicago had been the final hope for America and for Phil Ochs.” The album came out, Ochs’s first on A&M, with Ochs’s tombstone on the cover. On the back was a poem Ochs had written which began, “This then is the death of the American.” VI The Chicago DNC was one in a series of events that rattled American politics and culture in 1968. In February, a civil rights protest in Orangeburg, South Carolina sparked violence; three demonstrators were shot and killed by police. In March, students at East Los Angeles high schools staged a walk-out and issued demands for improvements in education, administration, and cultural appreciation. Later in March, students at Howard University in Washington D.C. organized a sit-in to protest outmoded, racist education and administration practices. On April 4th, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, prompting riots in cities around the country. Later in April, students protesting the Vietnam War occupied administration buildings and took three administrators hostage at Columbia University in New York City. In May, protests led by students at the Sorbonne in Paris effectively shut down the university and then the city, sending ripples around the world. On June 5th, Robert F. Kennedy, the presumptive Democratic nominee for president, was assassinated in Los Angeles. Having lost Kennedy, the Democratic Party resorted to nominating Hubert Humphrey, an old-fashioned Democrat from the midwest who had lost the 1960 primary election to Robert’s brother John. The protests and riots surrounding the Chicago DNC were in part a response to Humphrey’s nomination. Of course, they were also a response to the same unjust racial, educational, and military policies addressed by protests earlier in the year. In some sense, the Chicago DNC was for America what the May ‘68 movement was for France. Images of wild-haired, wild-eyed activists and folksingers being beaten up or arrested were both shocking and, somehow, unsurprising. The events in Chicago offered a powerful representation of what happened when American youths came up against their country’s curmudgeonly institutions and authorities. If these events were to serve as a culmination of protests by student and youth political movements in America, the resulting crackdown would signal the beginning of a widespread dejection and self-interestedness that would seep into the 1970s. VII During the summer of 1968, Elvis was busy planning and filming his comeback special. He met regularly with the special’s producers, Steve Binder and Bones Howe, and rehearsed set possibilities with a revolving cast of back-up musicians. Despite tensions between Binder, Howe, and Elvis’s manager Colonel Tom Parker, and despite the turmoil that seemed to be going on everywhere else, Elvis was very agreeable throughout the whole process. When Robert Kennedy was assassinated in L.A., just across town, Elvis “was practically beside himself,” as one biographer put it, but nevertheless he made it in for rehearsals that day and the next. The only dust-up involved Elvis’s wardrobe. Costume designer Bill Belew had designed a new gold suit modeled after the one Elvis had worn back in 1957. Elvis refused. Eventually Belew designed a tight black leather costume that was better-suited to the special’s tone. A similar adjustment was made to the finale of the comeback special’s set. All along, the Colonel had insisted on a Christmas song to close the show. But in the cultural context of 1968, such a finale wouldn’t make sense. Binder felt that the finale should say something about Elvis’s role in the changing America; it should be “a declaration of shared idealism” about America. Binder asked songwriter Walter Earl Brown to come up with something. Brown went home and wrote a topical song, an homage to Martin Luther King Jr. called “If I Can Dream.” The lyrics beg, “While I can dream, please let my dream come true right now.” It was released as a single with the B-side, “Edge of Reality,” and made $750,000 in sales. The special aired in December 1968, and was the number-one show of the season. VIII Between Elvis’s comeback special and his International Hotel stint, and between Ochs’s antics in Chicago and his performance at Carnegie Hall, a couple of English art school students performed as what they called “living sculpture.” Gilbert and George painted their skin gold, dressed in suits, got up on a small platform in the middle of an art gallery, and sang a well-known pub song written in 1932, “Underneath the Arches.” The idea was to show how one could become an art piece. In a statement accompanying their “Underneath the Arches” performance, Gilbert and George called it, “The most intelligent fascinating serious and beautiful art piece you have ever seen.” Along with that statement, Gilbert and George released some “Laws of Sculptors”: 1. Always be smartly dressed, well groomed relaxed friendly polite and in complete control. 2. Make the world to believe in you and to pay heavily for this privilege. 3. Never worry assess discuss or criticise but remain quiet respectful and calm. 4. The Lord chisels still, so don’t leave your bench for long. Like Ochs’s Carnegie Hall performance, it is hard to tell whether to take these laws seriously. Painter David Hockney said of Gilbert and George, “I think what they are doing is an extension of the idea that anyone can be an artist, that what they say or do can be art. Conceptual art is ahead of its time, widening horizons.” IX At the Carnegie Hall concert, Phil Ochs said, “Now we’re gonna do our next song, which is from Phil Ochs’s Greatest Hits, the greatest album ever put out in America, in which Phil Ochs has come from protest singer, non-media personality to the Elvis Presley all-time commercial plastic gold lame everything you want in America sexually, money-wise, credit-card-wise, Chase-Manhattan-bank-wise, and $5.50-Carnegie-Hall-ticket-wise, consumer-oriented star. Here I am. How do I get this way? I get this way...by way of being the American exponent, I am--I stand before you--the American, here I am the American. I wear my gold lame suit; I am the American. There is nobody more American, Richard Nixon included.” X So what the fuck. It’s actually pretty annoying to think about. Elvis was really the king. Phil Ochs was dead (not really). There was an inversion. Performance art helped it along. It turned the commercial into the artistic, and maybe it also turned the artistic into the trite. But maybe it was all already all the same anyway. What if—“What if I told you”—I told you that there was an inversion, or an intervention: by the time the masses were ready to accept and capitalize on folk far-out Lefty artist ideals, the folksingers, the lefties, the hippies and the yippies, the artists and all their ilk had gone commercial, embraced the commercial as the hope beyond abandoned hope, had turned gold. That change probably says something about the end of the 60s. By 1970, it had already been the 70s for a couple of years, and the 70s meant irony, pose, posture, appearances, the self over society, various cults of the individual, cult individuals, wars that wouldn’t end, giving it up. The dream was over. It wasn’t Phil Ochs, and it wasn’t Elvis either, or anybody who ever wrote for Elvis, but it was some other singer who was famous in the 60s and then basically went bananas off by himself who said, “I was the walrus, but now I’m John. And so dear friends you have to carry on. The dream is over.”

One last thing about Elvis, though: nobody could be who he was. It means a lot that Ochs tried. Ochs, the New York commie balladeer, singing about social responsibility, ethics, justice, current events, all of a sudden wishing he could be Elvis, seeing Elvis play at the International and realizing it could last longer than the Youth International, or even the Situationist International, and so wanting to perform as Elvis, create an Elvis Presley performance art piece for himself and for the greater good of society. It means a lot. Because it’s true, that throughout Elvis’s career he was always meeting with resistance from authority, from reverends to cops to colonels or captains, and there were a lot of times when those figures would end up saying something like, “Well, we’ve never had to do this before—but it’s looking like we’re gonna have to do it for Elvis.” And when those same guys got to know him, they couldn’t go on saying a bad word about him. How’s that for political power. And all the while, all he wanted to do was entertain.

0 Comments

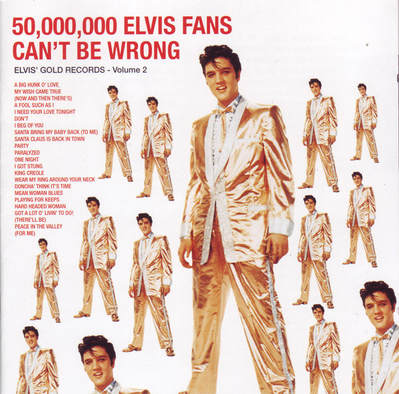

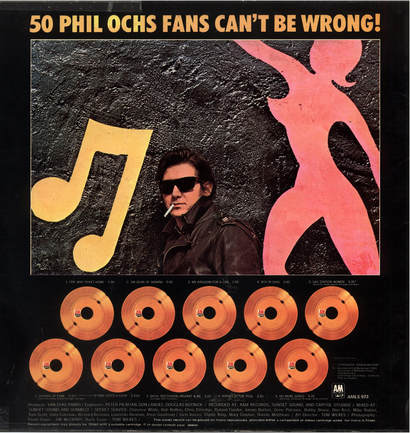

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Blog Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed