|

Written by Adam Iddings A ghost is a dead person for whom we have not yet finished with mourning. The Notorious B.I.G.’s 1997 album, Life After Death, is the recording of such a person. This piece is a speculation on Life After Death, and the ghost story that listening to it entails. I It was during my damned post-graduate year that I first heard of Life After Death. Let me take you down: I am in a shimmering hotel room at the Hermitage in Nashville drinking warm Bacardi from a cardboard cup. There is, all around, light glinting off of accent glass — the kind of glass that lays over nightstands and writing tables at hotels like the Hermitage. The sensation of being inside a chandelier is refracted by the floor-to-ceiling windows over by the bed. They look out onto what Nashville calls Legislative Plaza. It’s a place that memorializes the slain heroes of America. That is, the sirs and soldiers only. Look at ‘em. Biggie’s not there, of course — no space for him. But couldn’t he count as a hero? I can’t help but feel that inside this hotel room it’s like I’m being memorialized — not like transmogrified into an etching like the sirs outside, but more like acted upon by memory: I’m being made to memorialize. Memorializing kind of surrounds me; it conscripts me to uphold something or preserve something or receive something. Remember the slain heroes! You got it, Biggie, sir; just tell us how do we do it and where do we start. As far as ghosts go, Biggie’s is not your average ghost next door. The ghost we know and watch on TV and love leaves behind no traces. Sure he’s dead, maybe interred in the earth or, in Biggie’s case, collected as ashes in an urn, and so locatable as marker or nostalgia object. But to embody himself he rarely steps the evidentiary footstep into the foyer or the dusty parlor room. There are no prints or smears of the ghost next door. And here I am in this crystalline hotel room with all this glass for Biggie to breathe on or smudge. Instead, he’ll vibrate it if we watch. “I dunno why because I used to really feel Ready to Die but I’ve never heard Life After Death.” “Oh well here, let me put it on.” The sound surprises us by shaking everything. The window that looks out at Slain Folks’ Place blurs our spectral reflections from the shaking. Life After Death, the aural clue to communing with the posthumous B.I.G., suggests a ghost enough, and a vengeful one. Biggie must have known that to be a ghost he has to make himself heard as a ghost; his ghostliness depends upon being heard and not seen — being untraceable but also unquiet. Upon hearing it, we presume the ghost’s voice comes from somewhere beyond or at least after where we live, beyond the living; otherwise, how could it have shaken all it did. Of course the ghost lives in the afterlife, and so of course his being heard has to be loud and alarming. He lives a life plagued by reminders of unfinished business, beset by the past, harangued by never-to-be-requited desires. How would we feel, we wonder longingly at ourselves. And what do we do for these desires? Foremost among them is to be mourned. This French guy calls a ghost “A dead person for whom we have not done with mourning, who haunts us,” he goes on, “mistreats us, refusing to pass on to the other side... where the deceased accompany us distantly enough for us to live our own lives without forgetting them, but also without dying their own death, without being held captive again and again by their last moments.” Elegantly appraised, isn’t it? Elegiacally appraised even — a way of explaining that resembles a way of mourning, innit? But the thing is that to properly mourn the ghost, we have to listen to him, and how the hell do we explain or write our way into what listening is like? How do we hear what he wants and, hearing it, give it to him? Here is another French guy on the subject, insisting that, “The question perhaps merits a return: can one address oneself in general if whatever phantom already does not come back? If he loves justice even a little, the ‘savant’ of the future, the ‘intellectual’ of tomorrow is due to learn it [whatever that might be], and from the phantom. He must learn to live by learning not to have a conversation with the phantom, but to share himself with him or her. . . . They are always there, the phantoms, even if they do not exist, even if they are no more, even if they are no longer.” Well, the Hermitage Hotel is, after all, rumored to be haunted. But I don’t have any qualms about dismissing whatever older apparition in order to hear the ghost that was bigger and closer to me, bigger and closer than the Hermitage and its history even — something ancient about this B.I.G. haunting ghost — and I seek to hear him, to do him justice, to “share” myself, I guess, with him, and with you. That same last French guy, when he was not much older than I am, also posits that “To speak to someone is doubtless to hear oneself speak, to be heard by oneself; but, at the same time, if one is heard by another, to speak is to make him repeat immediately in himself the hearing-oneself-speak….” So in seeking to converse with Biggie’s ghost, I effect a hearing of myself. And if Biggie hears me, the ever-present ghost that he is, he repeats the effect of my hearing myself; I hear myself in Biggie’s afterlife. Finally, if you hear me getting all this down, then you repeat what Biggie repeats — namely, the sound of a guy rambling about ghosts from beyond the grave. So where does that put you, hmmm? I only know enough to say that Life After Death is not the record of the late Notorious B.I.G.’s life so much as it is the record of his afterlife. When we listen to Life After Death, we take our places in the auditorium of that afterlife. We apprehend something of that afterlife. In hearing Biggie ghosting us throughout his recorded Life After Death, we ghost our own lives such that listening to Life After Death entails hearing ourselves being haunted. I’m ascertaining as much without acknowledging it tonight at the Hermitage. We begin, counterintuitively in this case, with the beginning. And once it begins my brain is like a speedboat skittering across a lake. You know how it is, when something sets you zooming a million miles an hour. Mainly I’m thinking, “This dude is dead.” Zooom. The “Life After Death Intro” quashes any doubts about that fact. Probably the most incredible meta-means of introducing a man who really has, in real life, just died, the introduction sets Biggie in a hospital bed, dying. It could have been real! It could have been footage from the hospital in Los Angeles in whose bed Biggie really did flatline. Puff Daddy beseeches his profitable pal, “Live your life” while the heart monitor beeps in the background. Somebody’s gotta die, Puff, but life springs eternal. There is a hope, a light; there is a richness after death. Biggie attests to it on the next track, “Somebody’s Gotta Die.” His first line on the album is “I’m sitting in the crib dreamin’ about Learjets and coupes.” To die in Biggie’s underworld is to dream — and don’t the two altered states share a long but not necessarily amicable history. “For,” as old amicable Hamlet stipulates, “in that sleep of death what dreams may come / When we have shuffled off this mortal coil / Must give us pause.” It’s not the kind of dream we can dismiss as a cop out, in other words, but a dream that makes some sense of life and its end. Dreams lurk along the ridges of mortality, right? Cuz we don’t count them as life or lived unless we learn to, and we know they haven’t led us into an underworld unless only to bring us back out, if only to show us what it’s like and who’s down there. So how about the dream as our window into the afterlife, out onto Late Poets’ Square, through to wherever Biggie winds up after he flatlines. How about “Hypnotize”— the same theme, suggesting that Biggie’s words will hypnotize us into believing perhaps in his afterlife. According to one report, “Hypnotize” set Biggie’s funeral into a jubilant frenzy. However apocryphal, this story epitomizes at least one of the intentions of the album, if the first two songs are any evidence. We’ve got death, life, dreams, hypnotism; an introduction in a hospital room, a first song about death’s necessity, and a second song that seems to celebrate it. So in Biggie’s sleep of death so far, it seems what dreams may come must give us pause only before playing the next track and partying. And Hamlet would say here, “nay, it is; I know not ‘seems.’” And then, to paraphrase, “I am really genuinely bummed out about my dad.” Why do I keep quoting this play, anyway? I guess I’m quoting Hamlet because I think in tracing Life After Death’s tracks there emerges a line from Biggie to me to him — a triangulation at whose right angle he, Hamlet, is. Biggie’s death beckons his dreams for us to pause over, but that does not render his death dreamy or seeming — rather, Biggie’s death knows no seems because despite its being dreamy it is also concrete, factual, irrevocable. So Hamlet and his play are helping me out here. Like, remember in Act I of the play when Hamlet’s dad comes back as a ghost, bids adieu and tacks on there at the end, “Remember me,” almost like ye olde “I’ll be back” or an Elizabethan tragic Mufasa’s “Remember”— do you remember that? So Hamlet is a ghost story, too. And how Hamlet acts with the play’s ghost and enacts the ghost’s play can enlighten us I think to how to hear Life After Death, Biggie’s afterlife. When his father’s, the hero’s, ghost first makes himself known to Hamlet, he tells him to “Pity me not, but lend thy serious hearing / To what I shall unfold.” You got it pop; “Speak. I am bound to hear.” What do you know? So Big, we hear ya. I’m bound to hear ya, without blinking or flinching at what might happen after. Go on and kick in the door to our humble hermitage, serenade us tonight with tales of how you lived to your last day, how you loved your dough, let it show, and then learned what’s beef — the lessons there being the now idiomatic “Mo’ money, mo’ problems,” and the more humbling one about how we all bleed the same. Teach us; I hear, however far ahead, you’ve got a story to tell. II Now and forever afterwards I am drifting through fallen yellow leaves to an idyllic little elementary school. And I’m hearing “Somebody’s got to die,” “I’m gonna kill you motherfucker,” and “You’re nobody until somebody kills you.” I’m on the bus; the 56 makes for a nice way to speed through the city. It rides smoothly and keeps passengers cold. Its route bisects a cemetery whose barriers are too far off to see. And I’m on the damned bus searching for them. I’m on my way to work. Jaunting toward some ultimate encounter. Gliding through a forest of spirits to arrive at equanimity.

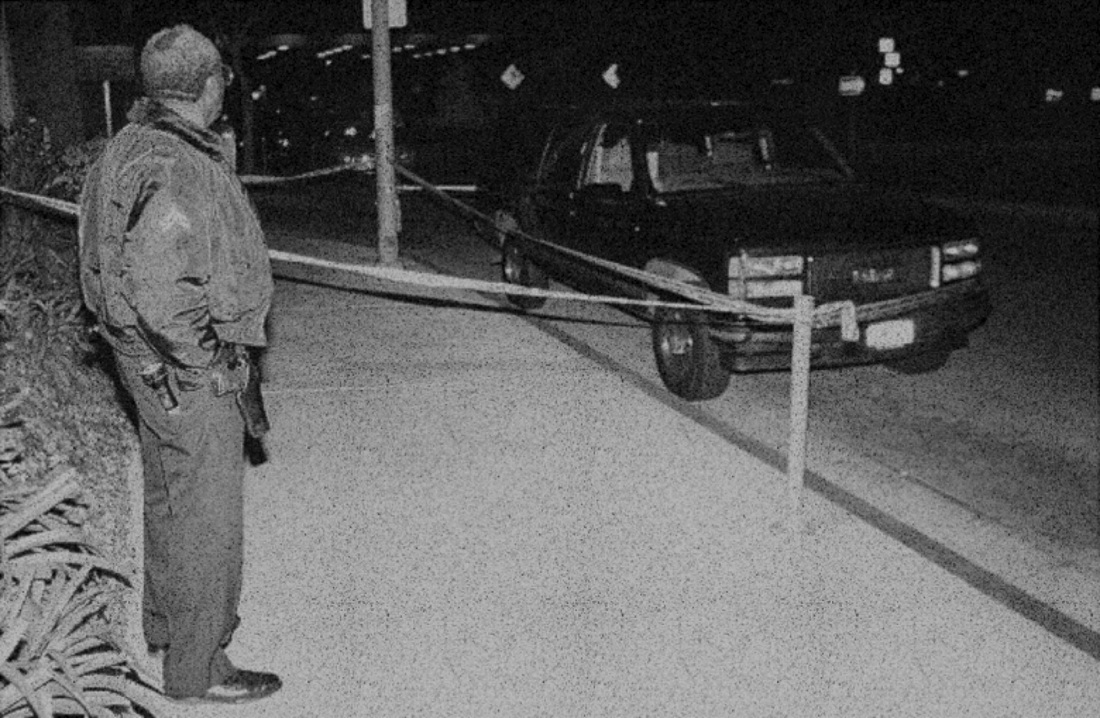

Oh right, I’m on the bus! Rather than cemetery walls, I see wasted distant tenements. In between the buildings stand signs for burger joints and Save-a-Lots. I am reminded for some far off reason of the Titanic slipping past glaciers in the night until suddenly it’s sinking. So what’s between this bus and those tenement buildings but a bunch of burial plots? And how uncannily does the scene resemble what Biggie saw in his Bed-Stuy? That latter question finishes the intermission between discs. “Notorious Thugs” comes on. I would later read that Layzie Bone’s verse was delivered in one take and fresh with sleep-slob. Bone Thugs allegedly brought to Biggie’s L.A. studio a case of Hennessey—six bottles of Hennessey. By the time Layzie Bone was slated to record, he had already passed out in some Band Manager’s van. The manager had to rap upon the window and waken little Layzie from his slumber, and then Layzie came into the studio and wrecked everyone. So I love this song. The way the delicate piano coincides with the lines “We gon’ rock the party” renders that expansive zone-out feeling sought by the song’s most blunted listeners. Then, at double-time and one and the same time, the lilt of one of the Bone Thugs guys repeats “It’s Bone and Biggie-Biggie,” and the high-hats and 808-skips click in, followed by a steady snare and flashing fat handclap. Finally around 50 seconds in, a low and deepening bassline. Bravo, Biggie, sir. According to that same source I’d later read, The Notorious B.I.G. was a little recalcitrant when it came time for him to record his bars for “Notorious Thugs.” He decided, “I ain’t laying mine. I got to wait. This style ain’t what I’m used to,” and went home. In such privacy, he prepared the verse we hear now, the verse I’m still hearing on the bus. And not a bad verse, for having been so unlike his style. But the Bone Thugs guys effortlessly illustrate how to handle those alien expectations. They crush the song in single file, one after the other, leading to a final rubble-reduction by the barely conscious Layzie Bone. I love this song; “it’s a damned masterpiece,” I say, on the bus. I get off the bus at a Church’s Chicken. I have a long trek ahead; however, it is a fortuitously beautiful Fall day out. The elementary school where I work is a half-hour ambling over bridges and through backyards. It is enough to imagine some Appalachian vacation town, and then imagine me walking in it with a backpack, steadfast. Meanwhile, I am myself imagining the California of “Going Back to Cali,” the fourth track on the second disc of Life After Death. Imagine that! What happened to land me here and not California, anyway? That is, how is it that I got out here to these sidewalks and yards, missing out on the sandy beaches and piers of the golden state? I put it plainly to myself, as Biggie does, “What’s your plan? / Is it to rock the tri-state? / Almost gold, five g’s a show date? / Or do you wanna see about seven digits, fuck hoes exquisite? / Cali: great place to visit.” What’s your plan, man? Is it to make ends meet working this lifeless job and eating Totino’s? Try to go westward while you’re pointed East? California sounds pretty appealing. Having been bereaved of my college life, I can’t cope out here in the Appalachian old South. Beautiful Fall day as it is, just this morning I noted how “Post-graduate life seems marred by the constant realization that this is what it’s like, that this is it, and that it is life, and that it is a real part of life. I find myself inventing meaning all the time, out of nowhere. I think of ways to meaningfully do whatever I’m doing or am about to do … I feel that life is in the process of becoming a perverse need — like the need to buy dishes on sale or day-old discounted bagels — a need to fulfill an obligation which I can’t and shouldn’t even strive to explain.” I’m stuck in the doldrums moaning, man, much like Hamlet, about growing more mature. “I have,” he declares, “lost all my mirth, forgone all custom of exercises. And indeed it goes so heavily with my disposition that this goodly frame the earth seems to me a sterile promontory.” So too have I been treading the trail with great black boots. In a few weeks for Halloween I’ll go as Death. I wear a bone necklace and dress in a tattered black cloak, and when a guileless swooner asks me what I’m supposed to be I tell her earnestly, “I’m Death.” Now imagine me, costumed as Death, dragging ass through the crumple on my way to work. There is no one around, just some birds perched staring from bare tree limbs. A couple tracks later there’s a creepy dude who breathes ravenously into Biggie’s phone, and then when Biggie hangs up he calls back and says “I’m gonna kill you motherfucker.” And as I’m walking I’m wondering like, who is this demon dude that hears Biggie spit and gets the idea, “I’m gonna kill you motherfucker,” huh? And the thing is — and I’m sure you already know what I’m gonna point out — somebody did kill Biggie. He was gunned down en route to an afterparty. At a stoplight, shot up sitting beside the driver of his Suburban. March 9, 1997 at 1:15 AM, two weeks before Life After Death. And we don’t know who did it. Just as I would at a later date read the Layzie Bone apocrypha of Life After Death, so too would I read about David Mack and Rafael Perez in the FBI’s thoroughly redacted investigation report. Biggie’s mom charged those two crooked LAPD cops with conspiring to murder her son. It has already been said that if we love justice, we’ll learn it from the ghost — except the Big ghost we hear doesn’t know anything yet either. That blissful ignorance is part of what makes it so unnerving to hear Big boast that “MCs have the gall / To pray and pray for my downfall.” There was certainly a lot of praying in the two weeks prior to Life After Death’s release, the two weeks after Biggie’s death. Eventually, the prayerful were or will be themselves released. Time marches on — like me, towards resolution. Let it all alone in the past, the urgency with which you strained to will The Notorious B.I.G. back through his aural last will and testament. Long kiss such listening goodnight. To sleep, perchance to dream. And you know, now I’m actually feeling pretty light. Floating, even, along the newly silken streets. Fall springs eternal again and the landscape is brimming with colorful warmth. There’s no wavering, there are no apprehensions. I traverse the bridge spanning the highway, and I disappear into the echoing: “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for you are with me.” The album has become an end, an artwork of itself that I can reach down and check out when I’m lucky enough to think to. It’s a thing recovered from history, gratefully, evoking a ghost story. I can clutch it as if it were a cloud, and it feels as delightfully featherweight and ephemeral as its big ghost.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

PLEASE NOTE: For the first two weeks of May, we will be revamping our blog sections and moving posts so that the site will be easier to navigate. Please pardon our (virtual) dust as we shift things around. Thank you!

Hip Hop Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed